This post reflects on my attempt, over about eight months, to bring smiles to people during the darkest hours of the COVID pandemic by morphing my lifelong hobby of performing magic for friends into short weekly Instagram and YouTube videos. All in all, my 32 magic tricks have been watched by more than three million people and liked over 100,000 times, making my attempt to use magic to bring brief moments of relief during those trying times somewhat of a success.

The insider story behind this effort hopefully will act as a satisfying epilogue for those of you who watched those tricks week after week and miss them. My road to success also ended up being a very difficult journey, and I believe the hard lessons I (re)learned along the way, while making mistakes, can help you succeed in your own projects, such as starting your own Instagram or YouTube channel.

Let’s kick off this retrospective with a highlight clip so you can (re)discover what this project was all about and, maybe, smile a little! :)

This post is organized as follows: First, I will provide a high-level overview of how the project evolved over time, listing the metrics I used to measure success so the story will be easier to follow. Then I will recount the project’s inside story, as it unfolded, from its origin in early September 2020 through its epilogue in April 2021.

I will talk about how the project came to be, how it almost failed as I took it in the wrong direction, and how I was able to turn it around and ultimately find success. Along the way, I will highlight the key lessons I (re)learned about how to drive a project to success, how I went about implementing my lessons learned in practice, and how they concretely helped the project ultimately succeed despite its disastrous start. It is my hope that these insights will help you, in your own projects, to avoid the mistakes I made and take a faster path to success.

Writing this post was very difficult, so I apologize in advance if the pacing and clarity is not as on point as usual—writing about something so emotional and personal is very out of character for me and I did struggle with it. The story is going to get a little dark at times, but please bear with me, as it was those difficult moments that led to the most important learnings and triggered the key decisions that ultimately led to the project’s success.

Of the 20ish lessons discussed in this post, I think the five most important ones are:

- Devising meaningful success metrics which is discussed in the “Overview section”

- Don’t commit without considering alternative options which is discussed in the “Origin section”

- Having a meaningful and measurable goal is the key to project success which is discussed from the section “Pitch black: November section till A new direction: early December” - probably the single most important lesson of the whole endeavor.

- Performing regular retrospectives it is the single most important way to steadily make progress is discussed in the section “A new hope: December”

- Recognize when taking a win and leaving the table, rather than doubling down, is the smart play which is discussed in the section “The last mile: April”

After reading the post, if you have a moment please let me know via social media or email which learning resonated the most with you. I am curious to hear different perspectives.

Let’s dive in! :)

Overview

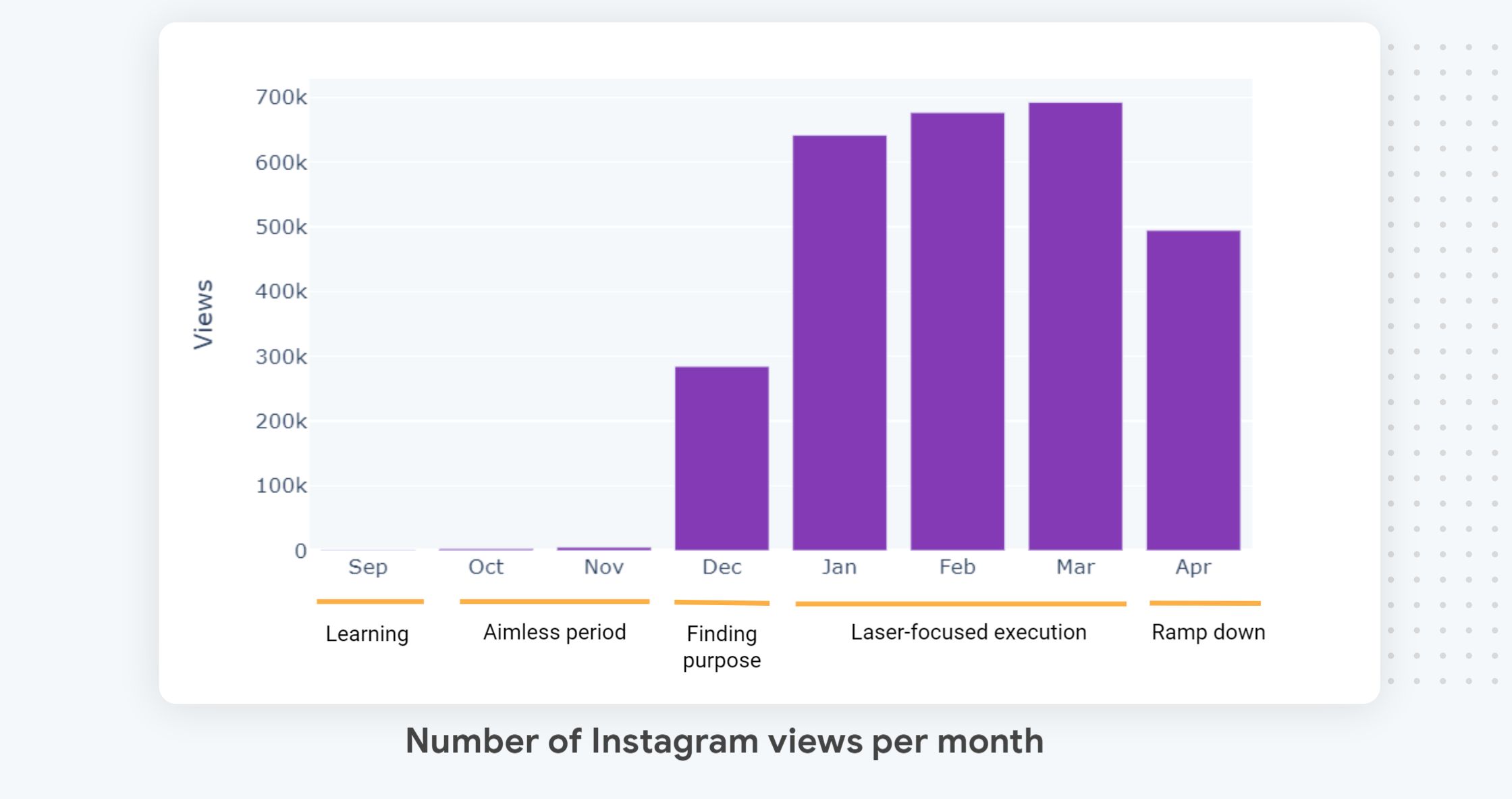

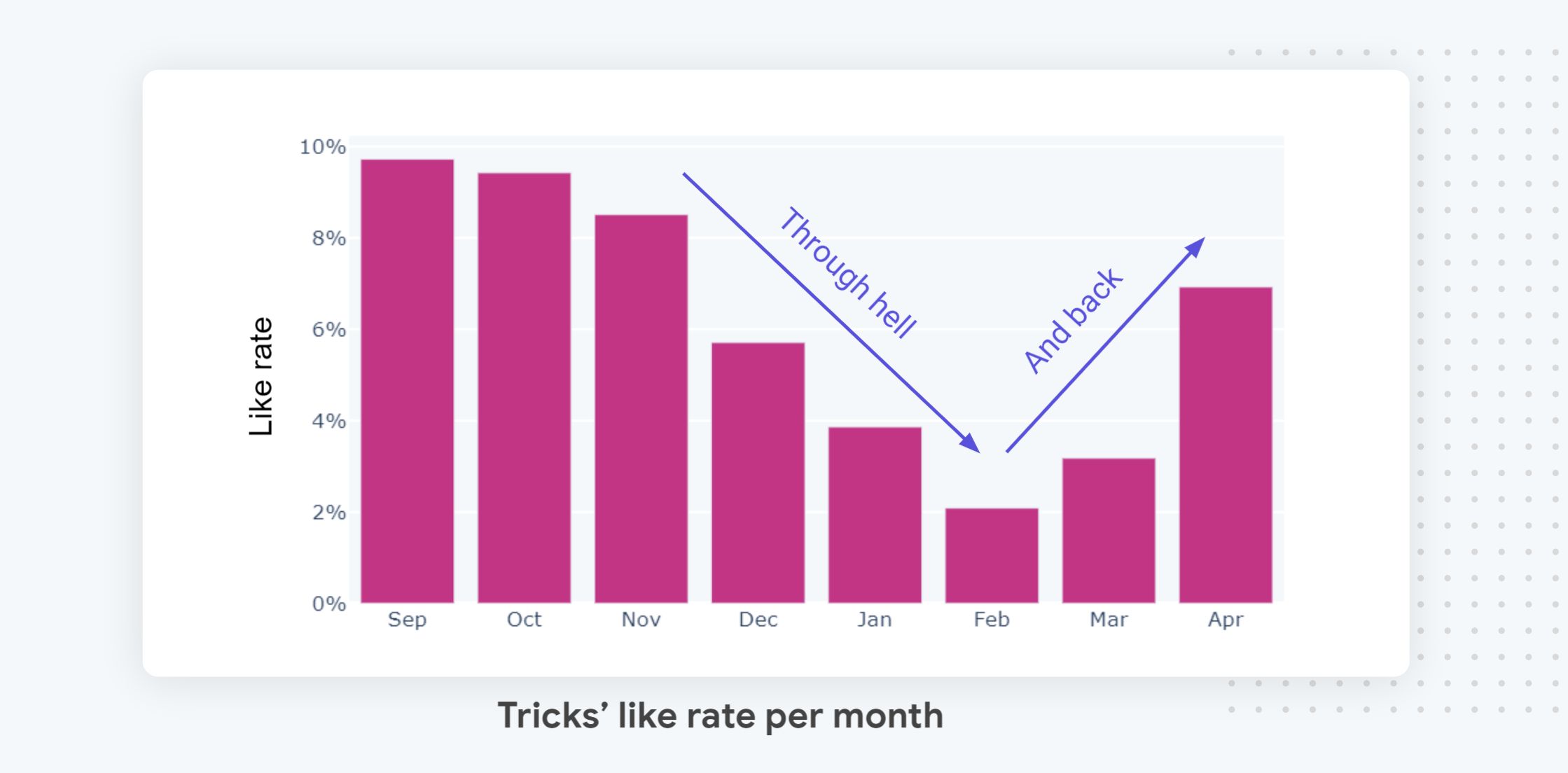

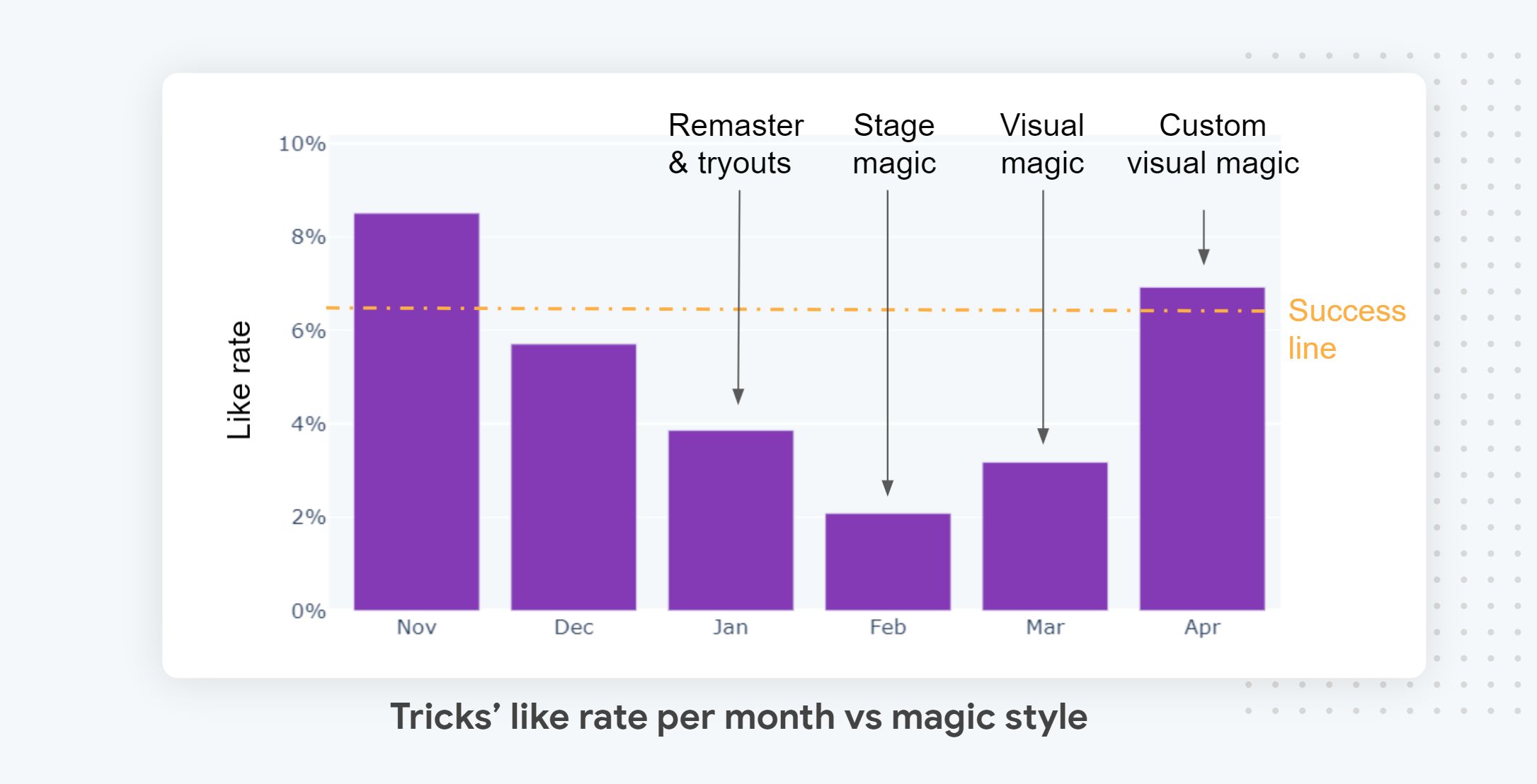

Looking back, I think the project can be divided into five major periods, which I have highlighted in the graph above, in my labels below the monthly project views on Instagram. I will spend the rest of the blog post discussing them in detail, but here is the gist of it:

-

September was the month when it all started and was mostly about learning how to do magic videos and making friends and colleagues smile.

-

October and November were the darkest period of the project. The audience grew from 721 views in September to 5177 views in November. This initial success blinded me and sent me down a rabbit hole. It’s during that time that I made my biggest mistakes, as the project didn’t have a true purpose.

-

December was a period of reckoning when I finally realized that I didn’t know why I was doing these videos and was able to find a deeper, more meaningful purpose for the project. The big jump that you can see in views is due to my decision to start advertising (a little) and its avalanche effect.

-

January, February, and March were the months when I spent all my energy trying to course correct the project. The views per month might give the impression that the project was already very successful, but it was not. As discussed below, view count in itself is not a good metric when your goal is for your magic to make people smile.

-

April is the month when the project finally reached its success target and I began to ramp it down. The view count is lower, simply because I only released three tricks that month. While ramping down as you succeed might seem odd, as you will see, by that time I was burned out. Ending on a successful note as the vaccines were rolling out made sense; it was a good stopping point. I think it’s one thing I got right: I knew when to call it a success and stop.

View count is not enough

As alluded to above, I decided not to use view count as my sole metric, because it didn’t capture how much people enjoyed watching the tricks. While not perfect, the best proxy metric I found to measure viewer enjoyment was the video like rate, which is the number of likes the videos received divided by their number of views: likes/views.

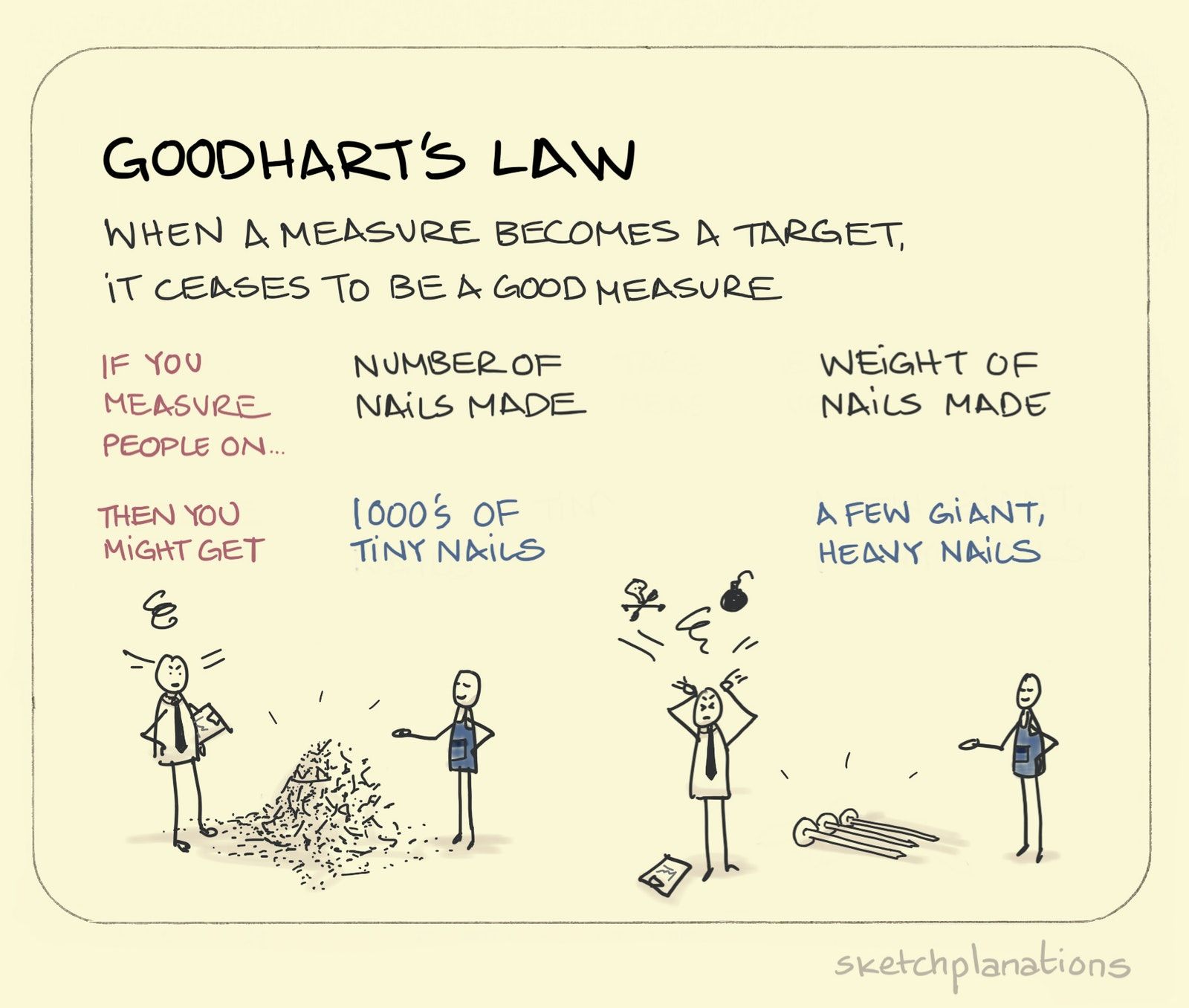

While you should never optimize for your metrics (Goodhart’s law), having meaningful metrics is essential to measuring progress, as you cannot manage what you can’t measure. In our case, if I had solely relied on view count, then I would not have realized, as I will show you below, that as the audience grew, the magic tricks that I produced were not as enjoyable as they should have been, and I would never have been able to correct that, making the project a failure. This is one of my mantras at Google: In our team, we don’t do research that doesn’t have a clear and measurable outcome. I think this focus on measurable impact is one of the main drivers behind our successes, from writing meaningful research papers (e.g Insights into The Right to Be Forgotten usage, Rethinking how to combat Online Child Abuse), to creating breakthrough technologies (Password Checkup, Gmail’s deep-learning malware scanner).

Establishing a baseline

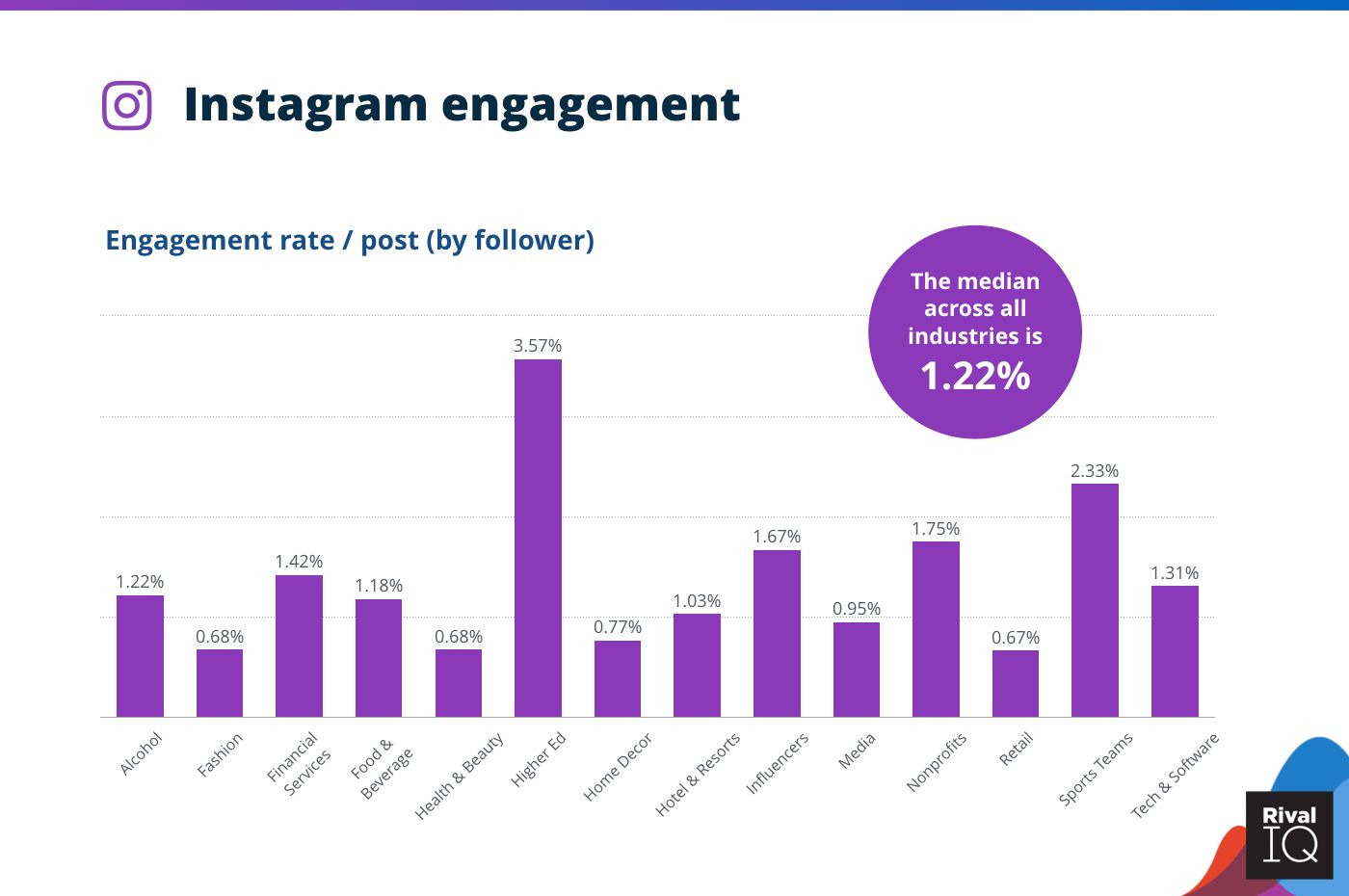

Now that we have a meaningful metric, the question becomes: What is our baseline? We need something to compare to. I found two possibilities online that roughly report the same number, as visible in the chart above. Rival IQ looked at Instagram engagement across various industries and found out that the average engagement rate is about 1.22%. While those averages are useful for setting expectations, they don’t tell us what we really want to know for this project, which is: What would constitute great engagement on Instagram?

Fortunately, FYI, Find Your Influencer, which specializes in allowing brands to find influencers (sigh…) provides a breakdown of various levels of engagement:

- Less than 1%: low engagement rate

- Between 1% and 3.5%: average/good engagement rate

- Between 3.5% and 6%: high engagement rate

- Above 6%: very high engagement rate

As you may have guessed by now, I decided, for this project, that to be successful, each magic video’s like rate must meet or exceed the FYI very high engagement rate (>6%) level.

Since the FYI and Rival IQ numbers are consistent, I believe they are at least partially representative of the true engagement distribution, which gave me confidence that meeting this target, in addition to having a large viewership, would meaningfully indicate that the videos and the project had accomplished their goal of bringing mental relief during the pandemic to many.

Project timeline revisited

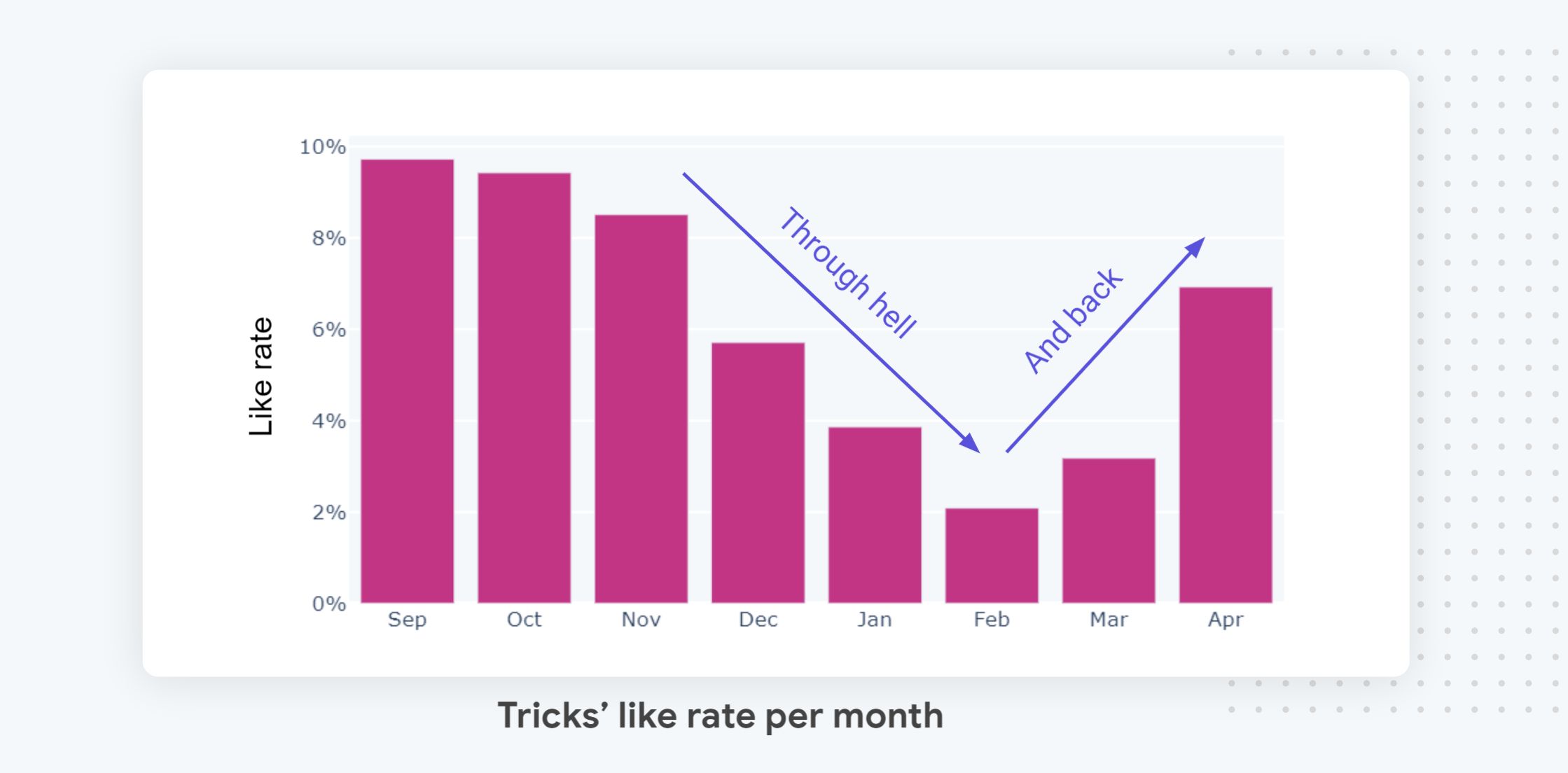

Looking at the project from the like rate perspective tells a totally different story than the view rate (which is why having the right metrics is so important!). The project started above its 6% target because friends and colleagues are very kind. Then, as the viewership exploded, starting in December, it became clear that my magic tricks were not suited to their task. While many more people watched them, they didn’t resonate with them, so the project was failing to achieve its target.

It took me four months of intense work (December through March) to understand and produce magic tricks that are enjoyable by a broad audience. During that period, as I will detail in this post, I approached the problem in a very systematic way that drew from my experience on how to drive projects to success at Google. To make this as useful and actionable for you as possible, I will explain the techniques I employed as we go along, so you can see how they were implemented and the effects they had in practice.

Origin story

Let me start by recounting how I ended up on this journey, so you can understand my state of mind and reasoning at the time the project started, as that greatly influenced many of the early important decisions made.

It all started during one of 2020’s darkest hours: late August when the pandemic was getting worse and raging fires forced many people on the west coast of the U.S., where we live, to evacuate. This deadly combo forced all of us to stay at home with nowhere to go, as you couldn’t breathe outside and everything indoors was closed due to lockdown.

In this claustrophobic atmosphere, I was on a video call with one of my colleagues, who, like many of us, was struggling with the situation, talking about random things, when they blurted out: “Can you do me a magic trick? I really miss those; They make me smile.” This request took me by surprise and I was unsure how to make it happen. In the end, I was able to cobble together a half decent trick by changing cards’ colors. That got the job done, but this was clearly not a great trick.

Over the next few days, this request got me thinking about the crazy idea that doing online magic tricks might be a good way to help my friends and colleagues who were going through the pandemic, by offering them a moment of fun and relief. As time passed, this thought stuck with me and It really felt like something I could do. In my usual overly optimistic way of looking at things, I vastly underestimated the difficulty of the whole ordeal and convinced myself to give it a go.

Now, there were several problems with the whole “let’s do magic tricks online” idea:

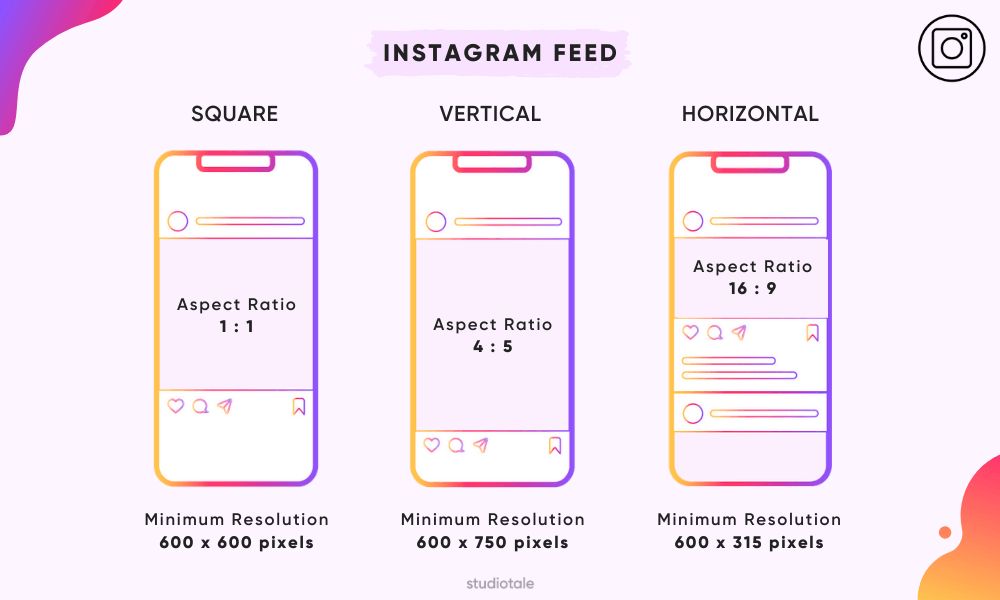

First, I didn’t have the equipment to do it, so I settled on using my phone and posting on my Instagram account that I had been using on and off without thinking too much about it. I didn’t realize it at the time, but deciding to use Instagram would shape the whole project due to the platform’s technical constraints, in particular, the need to create squared videos that are, at most, 60 seconds long.

In hindsight, there were a lot of alternatives I should have considered, such as TikTok or YouTube, and I should never have committed to a given platform/technology without looking into its market fit, even if it was only for friends and family, as selecting the wrong platform/technology for a project is a sure way to doom it from the start. This is why it’s important to write a design document with an “alternative options” section at the beginning of the project to avoid this type of mistake.

I must confess that I didn’t write a design doc for this project, and this was my first big mistake. I should have remembered that a project being personal is not an excuse to lower one’s standards: If it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing right. To this day, I am still not sure why I let my judgement lapse. I should have known better—I just didn’t :(

In the end, Instagram turned out to be a great choice, as there is a big audience for magic there and the platform’s very strict time constraint forced me to stick with short videos instead of attempting to create long form ones, which would have been unsustainable. I got lucky.

My second problem was that I had no idea how to do online magic. You see, magic as an art form takes many shapes, from close-up magic, to parlor magic, to stage magic, to online magic. All my life, as an amateur magician, I have been practicing casual magic, which is best suited for doing a trick for friends at a restaurant or colleagues during a meeting.

In particular, I had been following what Daniel Madisson calls the “no soap” principle, which refers to voluntarily making your card handling messy to lower people’s expectations about the trick in order to get a bigger reaction. Being clumsy with cards really helped me to get a bigger reaction in real life, as people did expect me to struggle with card handling, given that my day job is leading Google’s security and anti-abuse research team, not being a magician.

For online magic, appearing to be a klutz turned out to be a disaster because, as discussed in detail later in this post, to create a well-loved magic trick for Instagram, the main thing one needs to do is to make it very visual and impossibly clean looking—giving it an almost CGI-like effect. My lack of experience with pristine execution led me, over the course of the project, to spend a lot of time (up to five hours)_ redoing the same trick over and over till I got it right. Those long and frustrating repetition sessions vastly contributed to making the project time-consuming and at times a not so fun experience.

Learning the ropes: September

I published my first trick on Instagram, a card vanishing, on September 12, 2020. As you can see from the YouTube reupload above, the video quality is not good: It’s very grainy and a little shaky because it was shot with my phone held in place by a glass.

While I didn’t know it at the time, effect-wise, this trick had many of the key qualities needed to make a viral Instagram magic trick: It’s a short, very visual card trick with a clear plot.

Let’s call it beginner’s luck.

Behind the scenes, I learned two things while doing this trick that should have given me pause. The first was that it took me about three hours and 15 takes to get it right, which was way more effort than I had anticipated and I ended up exhausted. The second was that when I finally got to press the publish button, I felt an intense fear of looking silly and a deep sense of vulnerability—clearly not the feel-good moment I had envisioned. That should have given me pause, but I just kept going.

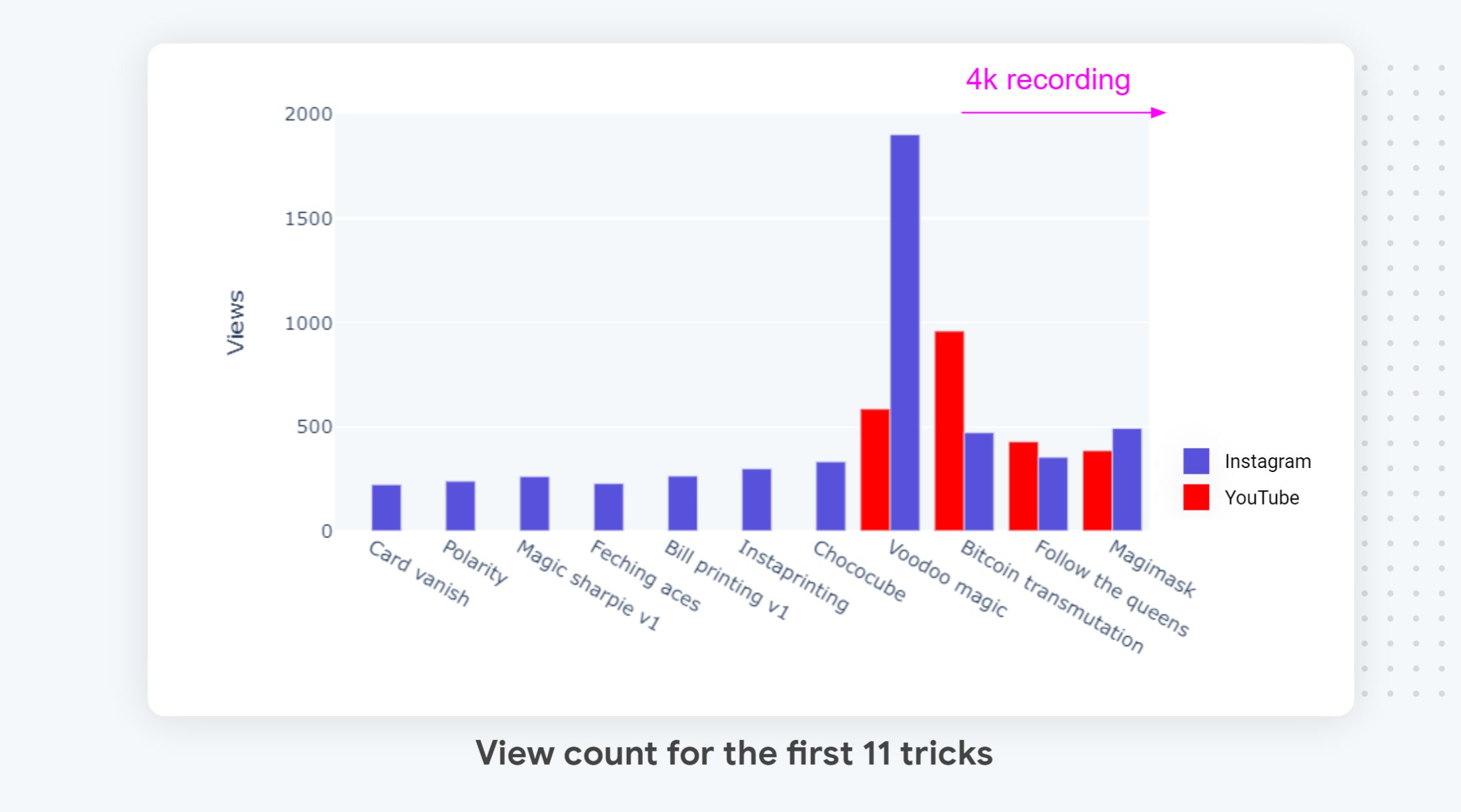

In the coming weeks, I pushed ahead and steadily recorded a trick every Saturday and published it on Instagram. As you can see in the chart above, on the surface, everything seemed to be going well, with the view count steadily increasing from 220 to about 500 after two months (doubling!) while the like rate remained exceptionally high by Instagram standards, hovering at about 9%.

Into the darkness: October

October was more of the same. I would think of a trick during the week, practice it a little, and then spend most of Saturday recording it and publishing it on Instagram. On the one hand, I felt a sense of progress, as the view count was rising and encouragement came steadily ( thank you 🙏). On the other hand, the effort was very time-consuming and started to take a toll on my other activities, such as blog writing. Perhaps more importantly, my senses of silliness and loneliness associated with performing tricks instead of receding , intensified each passing week.

I got my first “viral” moment at the end of the month, on Halloween, when I created a new magic trick specifically for the occasion, which you can watch the YouTube reupload above.

This lucky break, combined with viewers’ comments about the recording quality, led me to upgrade my setup, which you can see below, including buying a new camera, to be able to record in 4K and upload in 2K. After spending way too much time looking into it, I ended up buying a Sony ZV-1 because it was able to autofocus on objects, which was important since I was showing cards and other props to the camera. With those new capabilities at hand, I decided, on a whim, to switch to dual platforms and started to upload to both YouTube and Instagram from that point on.

Those decisions had a lot of ramifications that I didn’t carefully consider before acting, which was foolish. The main ramification was that I made the whole endeavor way way more difficult than it already was for very little additional impact. From that point on, every week, on top of practicing a new trick and recording it for hours till it was as flawless as possible, I had to create two videos, two captions, find suitable royalty-free accompanying music for the YouTube version, and design a video thumbnail for YouTube. This made the whole process much more strenuous, and often, I would start at 9 a.m. and was barely able to release the trick by around 11 p.m., or had to push it to early Sunday if I wasn’t done by midnight.

This insane amount of extra work, translated at the end of the project into a YouTube channel that only had 136,000 views and a like rate of 1%. Making the decision to have a YouTube channel gave me, single handedly, the worst return on investment of the whole project.

On the surface, it would be easy to attribute this bad decision to my lack of reflection around YouTube fit for short videos. However, there was an underlying bigger issue at the heart of many of the poor decisions I made: Two months into the project I still had not answered the key question: “What am I trying to accomplish?” As we will see, not answering this question not only led me to make poor decisions, such as committing to having a YouTube channel, but it also sent me to a mental hell of my own making.

Pitch black: November

As weeks passed, I started to cope with the increased workload by optimizing my workflow. I now had Photoshop templates with a cute avatar, visible above, that I could use to quickly create the thumbnails, a set of royalty-free soundtracks that I liked, and I started to record tricks in batches to minimize my setup time. While those improvements were nowhere close to the well-oiled production pipeline that I eventually set up during the second half of the project, they made weekly production bearable.

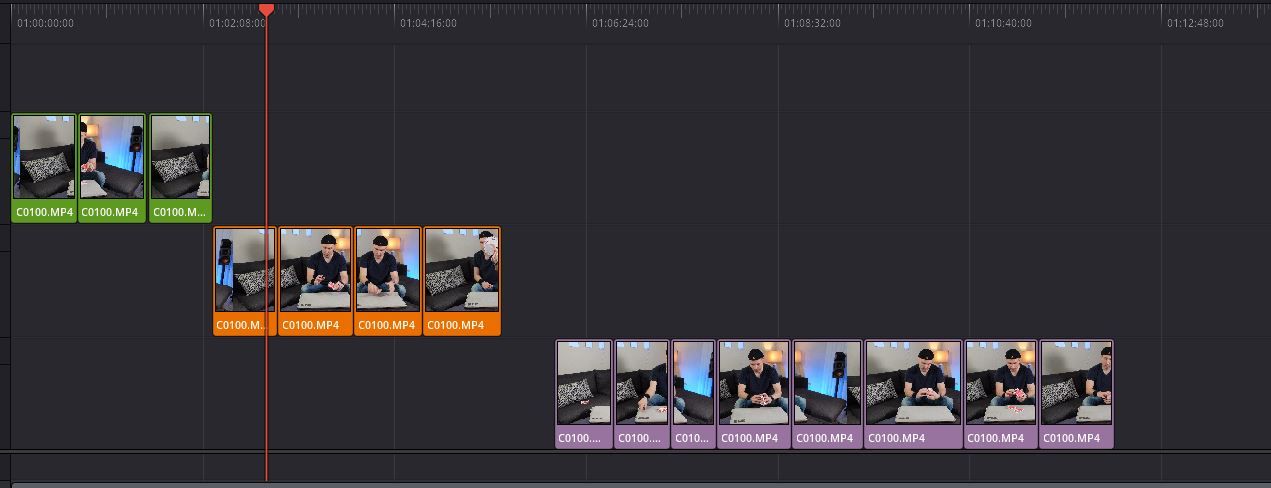

On the surface, the tricks I produced were getting better, at least in terms of execution and production value, as I gained more experience. My video editing workflow had become more streamlined and efficient. For example, to find the best take, I would, as you can see in the screenshot above, start by doing a rough cut of all the takes I had made for a given trick (15 in this example) and then watch those in rapid succession to sort them into three buckets: good (green), maybe (orange), and visible errors (purple). From there, I would select the one I liked best and focus on editing it.

Underneath this increased quality, I had made the situation worse without realizing it just yet: As the tricks started to reach a broader audience, who didn’t know me, their visual quality, such as the very professional intro, created an expectation to see awesome magic tricks.

However, awesome magic tricks were not what the audience was getting, as I didn’t have, at that time, the experience and processes in place to produce those, and I failed to meet the audience’s high expectations. For example, at that time, I was releasing tricks without having friends performing quality control, which led me to publish a few tricks that included massive blunders, such as the one shown above where I flash the coin 😳. Those sub-par tricks rightfully got me really negative comments/dislike from the audience. The project had reached one of its lowest points.

Between the lack of purpose, the blunders, the negative comments, and the heavy workload, I began to dread weekends and had to reach deep within to keep going. Every week, I would sit in the living room feeling lonely and silly as I recorded take after take for each trick. It became so difficult that I clearly remember not being able to even look at the camera between takes, as you can see in the still above. In late November, I finally faced the hard truth: This project was bringing me to my knees and something had to change.

Facing reality: late November

Now that I had finally come to terms with the realization that I had a problem, things got surprisingly easier, as now “all I had to do” was solve a crisis. It turns out that crisis management is something I have become quite good at, as it has been a major part of my job since I joined Google, because it’s part of helping fend off the attacks targeting Google users and products. Being on the frontline is very important for our research team, as it exposes us to the most pressing/hardest problems faced by users and helps fuel our creative thinking. For more on this topic, you can check my blog post on how we helped take down one of the largest Android botnets, Googligan.

The hardest part of a crisis is understanding its root cause and what it would take to change the situation, which is why I spent a good chunk of my late November evenings walking outside, trying to understand what went wrong. Getting to the root cause is a delicate process, because if you stop thinking too early, you might end up confusing a symptom with the root cause itself and solve the wrong problem. Spend too much time diagnosing the issue and you end up losing precious moments when you can least afford to.

For this project, my initial analysis led me to realize that I didn’t know how to do tricks that please a wide audience, and at first I assumed that that was the problem. As alluded to in the overview section, there was indeed a gap at the time between what I thought was a good magic trick and what the audience enjoyed watching. However, going deeper revealed that this disconnect was not the problem itself, it was just a consequence of the underlying issue, which was that I didn’t know why I kept trying to make better magic tricks and reach more people.

The project had exceeded its initial scope of making friends smile and had morphed into a much larger effort with no clear goal or metric. I was just mindlessly making it more complicated for the sake of doing more.

Once I arrived at this conclusion, I became really angry with myself for making such a mistake. Ensuring that each project has a clear, measurable, well understood goal is one of the tenets that I practice assiduously and I should never have pursued an aimless project for months. Things had to change.

A new direction: early December

Once I clearly understood what the problem was, I was finally able to sit down with myself and reflect on what was driving me to keep going despite the project being such a burden. First, I asked myself if it was a false sense of pride that kept me from giving up, but it was not that. Then I steadily enumerated all the obvious motives I might have, from wanting recognition to fear of loss, but none of them felt like they were my main motivating driver.

Reaching deep into my soul, I discovered that seeing suffering all around the world deeply made me want to do something about it and that something had to be tangible. Magic had become my way of doing this, and I couldn’t let go of it.

I knew that in the grand scheme of things, I was not providing much help, and that I had more efficient options in which to invest my time and money, including making larger donations and doing more overtime at Google. However, performing magic was a much more personal and direct way to help, and that was important to me. The little words I had received about the magic tricks, such as this friend from afar telling me that the tricks had helped him to stay sane, mattered dearly to me. Those kind messages made me feel connected to the world and I just couldn’t give that connection up.

This project is one of the few cases where I have shied away from effective altruism, because it would have made my life very dry. One could make the case that mental health had become a widespread issue during the pandemic and that this project effectively helped with this. At the time, I knew some people who really struggled mentally, but I didn’t realize how prevalent the issue was, so I can’t take credit for making an effective choice. I am just glad that in hindsight, this choice makes even more sense than it did at the time when I decided to go for it.

With this newfound deep understanding of why I was doing the project, I was finally able to clearly articulate a meaningful project goal: From that point on, no matter how much effort was required, I would bring as many smiles to the world with magic during the pandemic as I could. I promised myself to only stop when the situation had cleared up. Snow or rain, a new trick would be released every week, and because I truly believed in the project mission, I was able to keep it up till April.

I knew this commitment would take a toll, because it would be in addition to my commitment to my team, Google users, and the charity work that my wife and I were already doing. To mitigate the issue as much as possible, I did what you’re supposed to do in every crisis: Depriotarize everything that is not essential. I stopped writing for my blog completely, to free up my Sundays (sorry about this—I just couldn’t do both), repurposed all my fun budget for the project (e.g., sold my PS4, and never attempted to buy a PS5), and adjusted my schedule so I could get up between 6 and 7 a.m. every weekend and holiday morning to have as much time as I could for the project.

Those might seem like extreme measures, but given how difficult the project was, I knew I needed that type of commitment if I was going to have a chance to succeed. More generally, people are often reluctant to take drastic actions to resolve a crisis, but in my experience, this is how you get things resolved.

You cannot manage what you cannot measure, so now that I had a goal and a deadline (till the vaccines rolled out), I needed to make it measurable. In November, I did reach about 3500 people, so I went for the 100X goal and decided that I would try to get to 350,000 views per month, which I estimated would lead to at least about 1M views during the project lifetime, as the vaccines seemed a very distant prospect at that point (December 2020).

One can object that views do not equate with smiles and I agree with this. So as a proxy for enjoyment, I added the extra constraint that the tricks’ like rate would have to be extremely high. As discussed in the overview section, an extremely high engagement for top influencers is 6%, so I adopted this number as my like rate target.

You would think that adding an extra constraint would make it harder, but metrics must be as meaningful as possible so you are confident that you are making progress. The better the metrics, the more truthful the feedback you get, and the faster you can improve. If you want to be successful, don’t settle for the obvious metrics, devise meaningful ones.

As I discussed at length in the overview section, and as visible in the graph above, if I had solely focused on view count and not used the like rate as a top of the line metric, I would have missed the vital fact that people didn’t enjoy the tricks and the whole project would have been meaningless.

The corollary of the rule to use meaningful metrics is also very important: If you can’t find meaningful metrics that directly measure your project impact, then it’s likely that you are solving the wrong problem. Early in my career at Google, we did a few projects without defining clear success metrics, and every time that ended up poorly. Either we had to course-correct mid-flight or the project was a failure.

It was now December and the project finally had a clear goal: Generating 1 million views and 60,000 likes (6%) by releasing tricks every week for the next few months. Now, to be clear, at that point, I had no hope to reach that target. On the contrary, I felt it was out of reach, but at least it was meaningful: If somehow I could hit it, then the project would be something that would have made a meaningful difference. I was far from imagining that the project would reach 3 million views, over 100,000 likes, and that some of the tricks would end up clearing the 8% engagement bar by the time the project wrapped up. At that point, I had 15,000 views under my belt and a dream with a deadline.

A new hope: December

I started the month of December with a renewed focus and finally had a sense of purpose. To help each trick reach a larger audience, I decided that, from that point on, I would spend a small amount every week advertising on Instagram and YouTube. The amount did vary over time, but it was never more than a few dollars per day. Advertising the tricks gave me the chance to run ad campaigns, something I had never done seriously before. Online marketing happened alongside video editing and animation creation, becoming one of the skills that this project allowed me to strengthen. In general, I strongly believe that the chance to learn and apply new skills is one of the most important benefits of doing a new project and this is why it’s important to always aim to do projects outside your comfort zone. I will talk more about my experience advertising the tricks later in the post.

I had high hopes for the first trick I did that month and truly thought people would find it “awesome and funny”: I made a physical Bitcoin appear inside a glass jar. This trick turned out to be a disaster: As you can see from the video above, I didn’t show the inside of the lid before closing the jar (I could have but didn’t) so people assumed that the coin was in the jar and hated the trick. They rightfully called it too simplistic. This was clearly not the outcome I had hoped for.

Part of treating this effort like an important project meant that I did allocate time to do a weekly retrospective once the numbers were-in. Every Friday night I would take about 15 minutes to reflect on what could be improved on moving forward. In my experience, performing regular retrospectives focused on figuring out the most important thing to improve and how to improve it is the single most important way to steadily make progress. I do retrospectives for everything I am serious about, from research, to financial planning, to public speaking, to this site, to physical training. I always want to have a clear idea of what I must do better to be more successful. This can only be done if you have meaningful metrics to guide your thinking, which is why, as I said earlier, it’s important never to cheat when you define your success criteria; everything depends on it.

Accordingly, for the first retrospective, I took note of that failure, and decided that moving forward, to fix the issue, I would need to add quality control before releasing a trick. In hindsight, it is obvious that, just as code must be reviewed before being merged and text must be proofread before being published, magic tricks should be reviewed before becoming public, but I didn’t realize that until that point. From then on, I would ask a group of volunteers to review tricks and rate them.

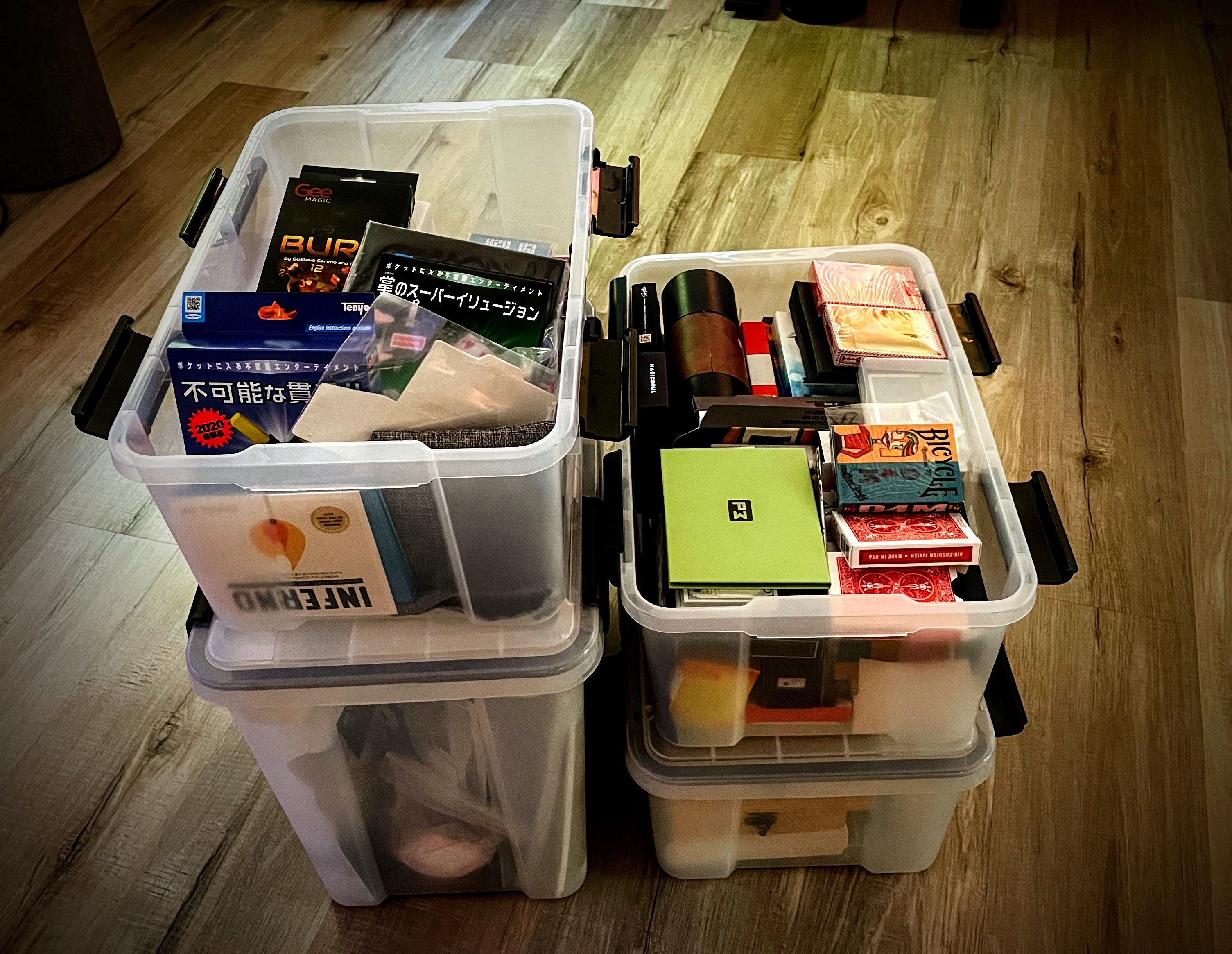

The need to implement quality control made me acutely aware that working on a trick by trick basis and constantly running against the clock was not going to be sustainable. For example, this prevented me from doing serious quality control because, beyond reworking the cut, or fixing the audio, my margin of maneuverability was limited. I simply couldn’t afford to scratch a bad trick or do more recordings of it to fix its flow. I figured out that my best option to solve this was to take advantage of the end of the year break to fix the situation by recording many tricks in advance. Coming up with this plan early in December, as you can see in the image above, gave me enough time to order many tricks from various magic resellers so I had plenty of raw material to work with during the break.

The other key lesson I learned that month was that I clearly didn’t have good intuition about what tricks the audience would like. This was made painfully obvious by the engagement rating, which dropped from 8.5% to 5.7% that month. Figuring out the right formula was the single biggest challenge I would face for the rest of the project.

A project reborn: winter break

The winter break at work from December 20th through January 4th gave me the reprieve I needed to get organized and set up the project for long term success. In particular, it gave me time to record many tricks in advance and build the buffer I needed to do things in batches moving forward. From that point on, I was producing about four tricks at a time.

Creating a visual identity

During the first week of the break, I focused on creating an improved visual identity for the channel that would help it in two ways. First, it would convey that the videos were supposed to be fun and friendly. Second, it would allow me to express feelings while remaining silent. Since the beginning, I had made the conscientious choice to perform silently to make the magic trick universally understandable. Initially, this decision came from the fact that I had friends and colleagues speaking various languages and I wanted to do magic for all of them and their families. Later, as I scaled up the project, this choice became even more important, since I wanted to be able to reach people everywhere around the world.

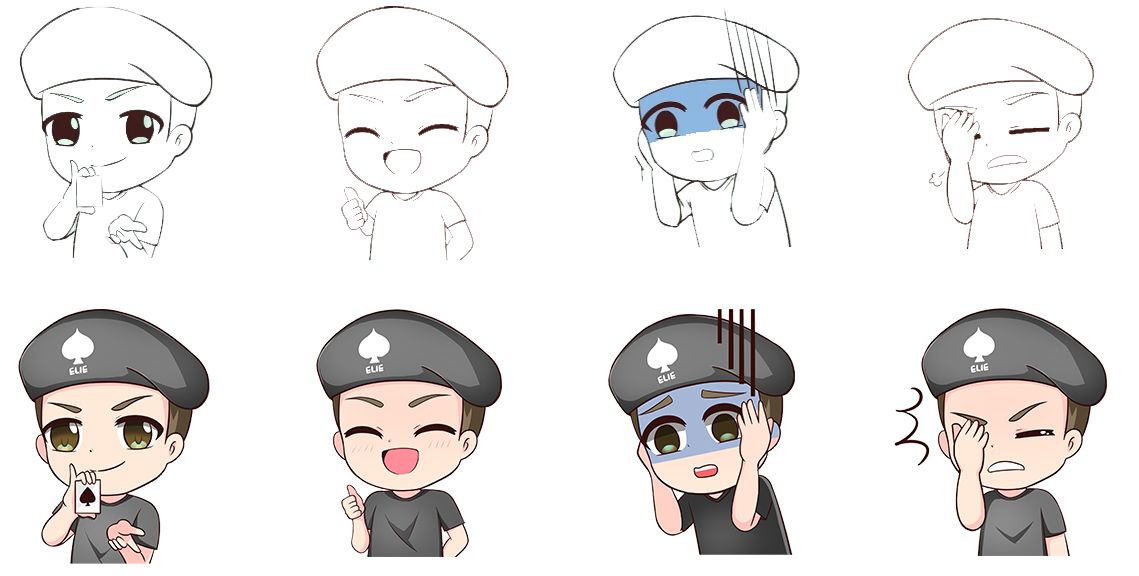

A key challenge with being silent is that it limits what can be expressed. To mitigate this issue, I worked with Clara, a Fiverr designer, to create many variations of an avatar that would allow me to express feelings in a fun way. For example, as you can see in the screenshot above, I would routinely use it to express success, stress or failure.

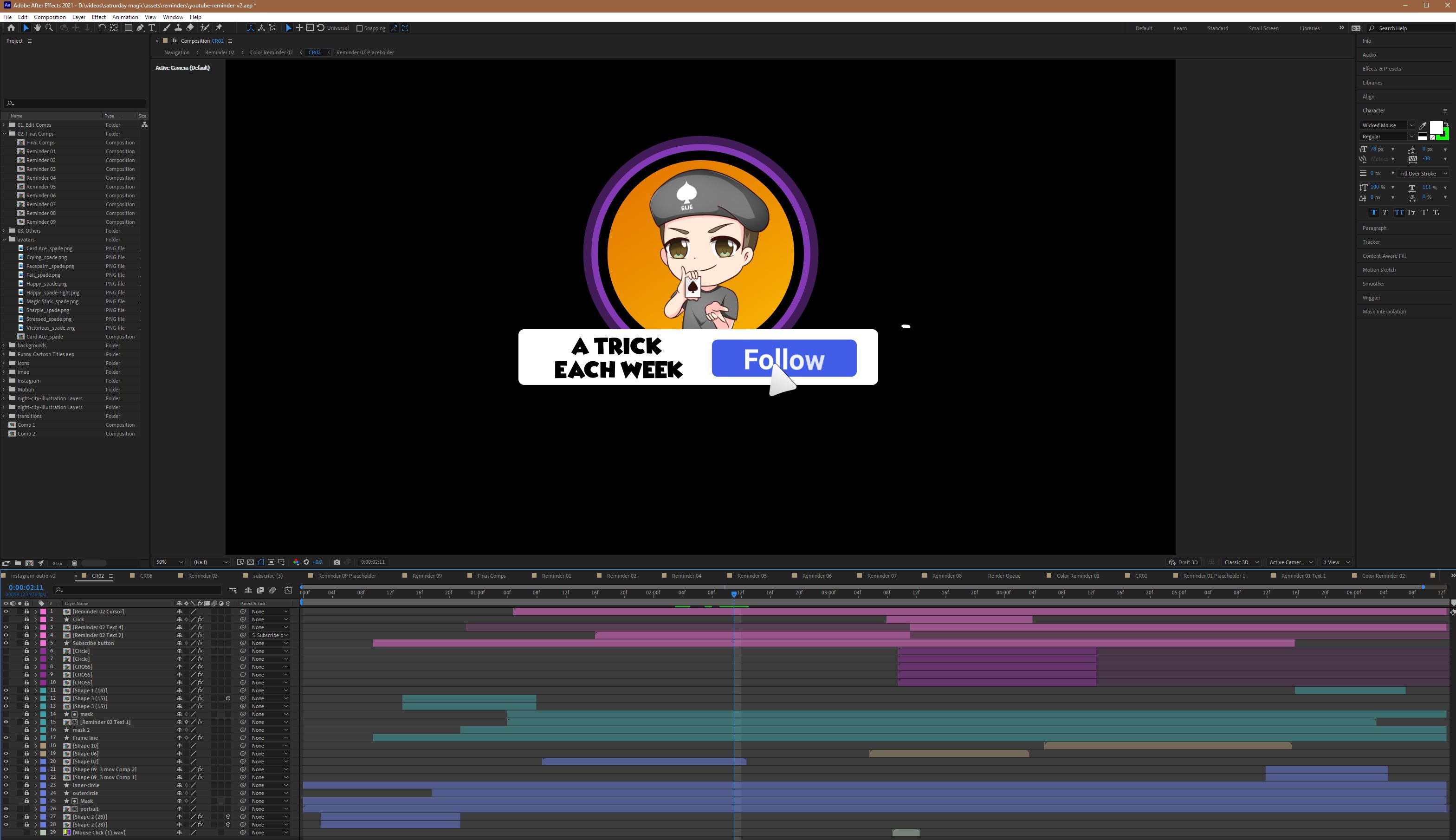

I then spent more time than I care to admit learning how to create the like/subscribe/end of videos animation I needed. On one end, this gave me the opportunity to learn how to use Adobe After Effect, which is something I had wanted to do for a long time. On the other hand, I probably overdid it :)

The down side of this improved identity was that it made video editing even more intensive and time-consuming. As you can see from the screenshot above, which is the Da Vinci Resolve timeline for the Magic bunny trick, I now had many audio tracks and video tracks to account for the visual effect, reminders, and the intro/outro. The backbreaking part was that I had to manually change/resize all the video effects when switching from the YouTube format (16:9) to the Instagram one (1:1).

Establishing quality control

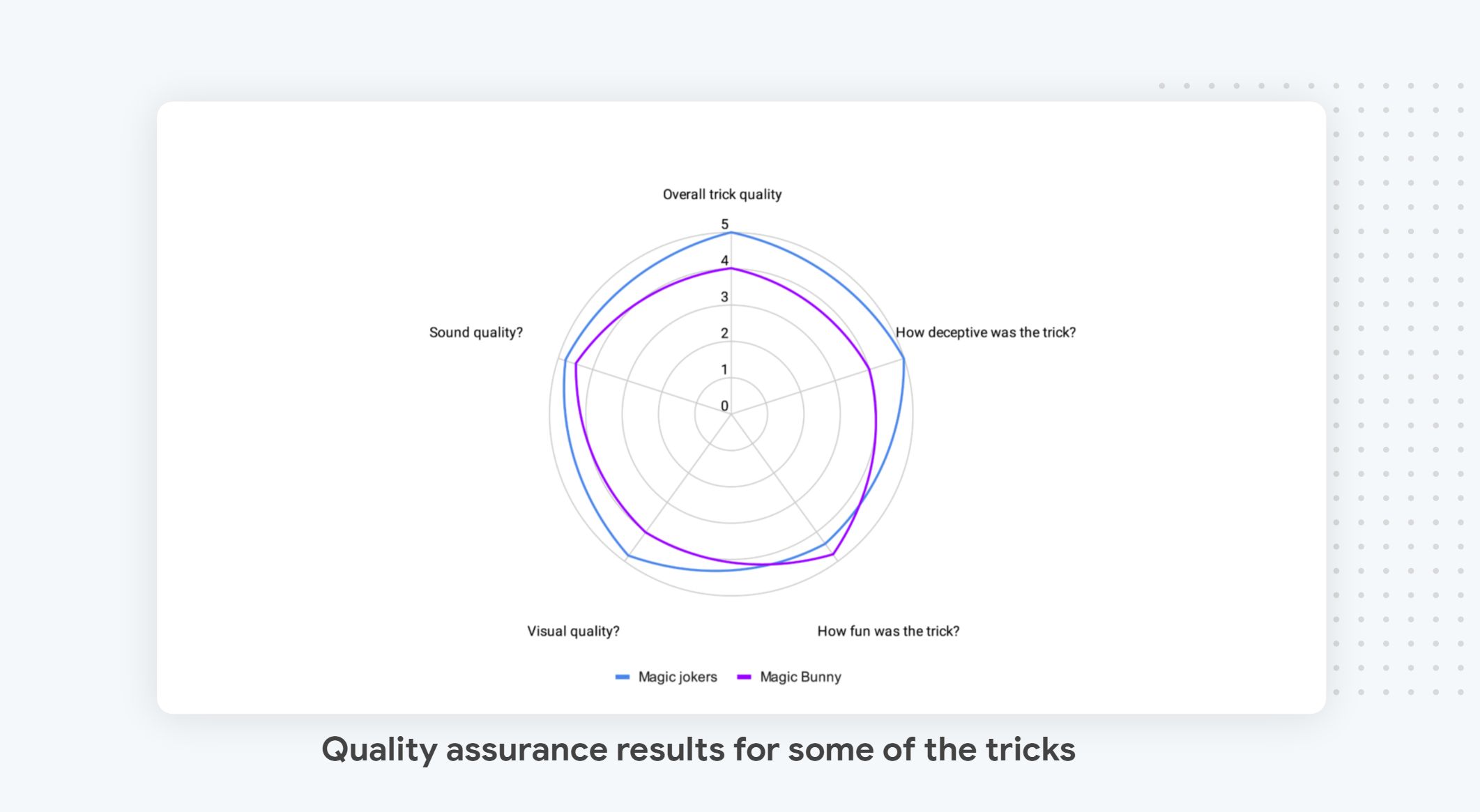

This buffer of tricks gave me the ability to implement true quality control, where I would ask from 2 to 4 volunteers to review tricks, and rate them on key aspects using Likert scales. As you can see from the chart above, which shows you the reviewers’ ratings for two different tricks, I would not only ask about the overall quality of the trick (5 being very good, 1 being awful) and technical scores (visual and sound quality), but also about what, at its core, makes a good trick, which is how deceptive it is and, finally, how fun it is, because we were optimizing for smiles.

Each of the survey questions asked were carefully designed to turn the answer into actionable feedback. For example, there was one trick that had an audio quality problem, with the audio effects being not loud enough, and I was able to fix it by redoing the audio arrangement. For one trick, the QA surfaced a visual quality issue, which turned out to be due to me inadvertently cutting a few frames out while editing the video. This erroneous deletion created the impression that the trick had been edited to hide something, which had not been the case, as the project was about using sleight of hand, not CGI effects.

In general, when designing a survey, the most important question you need to answer is how you can turn the questions’ answers into something useful for your project. Resist as much as possible the temptation to ask curiosity-driven questions, as they are a waste of the most valuable resource of all: people’s time.

The most difficult quality issues to resolve were when a trick was flagged as not deceptive enough, as there was no easy fix for those. Instead, I had to jump on a call with the reviewers to try to understand why they were not fooled by the trick and try to figure out if I could fix it by rerecording the trick or if it was just not good enough and had to be discarded.

While that might sound extreme, being deceptive is usually considered to be the single most important quality a magic trick must have, according to magic theory, for the following reasons:

- If it’s easy to figure out what will happen, then the astonishment factor, which is at the core of the enjoyment, is gone. Instead you get a sense of “I told you so”.

- If it’s easy to figure out how the trick was done, then people are disappointed and feel as if they wasted their time.

As alluded to earlier in the post, I did release non-deceptive tricks, and that is exactly what happened, so non-deceptivity was a strict no go and if I couldn’t find a way to make the trick more deceptive, I did discard it, even though doing so was particularly painful.

All in all, I ended up discarding nine tricks, which amounted to at least 50 hours of work that went straight to the trash bin. Some were just too obvious, like making water vanish in a newspaper. Others, like one of my favorite tricks, the Torn and Restored Playing Card trick, simply couldn’t be done in my preferred way in front of the unwavering camera eye.

By the end of the winter break, the project had been effectively Taylorized with clear production planning and reusable visual assets. Having a few tricks ready in advance, combined with the efficiency gained by working in a batch, made the workload much more manageable and gave me the opportunity to be strategic about the project rather than reactive. The video above shows you how far the project had come in terms of production value by showing, side by side, the initial version of the Sharpie trick I did with my iPhone back in September and the version 2.0 that I released on January 2 as the first trick with the new visual identity.

All that was left to do was to steadily apply the new process and figure out the type of trick that worked best on Instagram to succeed. Little did I know that it would take me almost till the end of the project to get there.

S is for science: January

A magic trick, to be great, needs to make the best use of the setting in which it is performed to push the limit of what is possible. This is why magicians tend to group tricks based on the settings in which they are meant to be used, with the most well-known being close-up magic, parlor magic, stage magic, and online magic. The rub was that the type of magic I have been practicing my whole life, mentalism and close-up magic, was meant to work well in small settings, such as bars, restaurants, and meetings, not Instagram.

Until December, with the exception of one or two tricks, such as the Magic Sharpie one discussed earlier, I mostly tried to adapt tricks that I love to do in person. This approach was not working at all: I ended up spending a lot of time adapting tricks that ended up going over Instagram’s 60-second limit, while not being interesting because they lacked a narrative or were simply not visual enough. It was time to switch things up and find the most effective type of trick to perform to maximize audience satisfaction.

To figure this out, I was hoping to be able to rely on the scientific method, where I would treat each trick as an independent experiment that would test an idea (hypothesis) and see if it would improve our top of the line metrics: Instagram like rate and views. I would then “just have to” iterate and refine the formula till I reached success.

I started down that path by testing whether the early project successes could be reproduced with a larger audience. I did that by “remastering” two tricks that got high engagement when I released them early in the project: the Magic Sharpie trick and the Bill Printing one. If these remastered versions also had a high engagement rate, that would mean that success was due to something I did right, and it was just a matter of understanding what it was. If not, then I would have to accept that what I had done so far was a fluke and would have to restart from zero.

The results for the Magic Sharpie trick came back positive: The initial run had 261 views and a 10.7% like rate, while the remaster got 92,001 views and an 8.6% like rate: not as high as the initial run but significantly higher than our success bar of 6%. 🎉 Success! At least the enjoyment side was reproducible; I just had to crack the code to make it repeatable :)

“What happened with the Bill Printing trick?” you might ask. Well, it bombed… With 181,087 views, it got only 4509 likes, an okayish 2.4% like rate 😢. The issue with that trick was that the caption I wrote, “Making money the magic way”, triggered Instagram anti-abuse filters and pushed the trick to the low quality bucket (the irony of the situation not being lost on me). This demotion led the trick to have an incredibly high view rate (twice as many views as the Sharpie for the same amount of advertising money) with an ad engagement rate that was through the roof (I think it had about a 60% display to view ratio), but this also biased the audience, so I discarded the data while making note during the retrospective to be mindful of my captions and acknowledging that luck would play a big role (no surprise here).

From that point on, I recorded everything I could about each trick, from the type of prop I had used (cards, bill, coin…), to the type of effect I was trying to achieve, to the type of magic it was, to its QA scores. Every Friday, I started the weekly retrospective by looking at how varying specific conditions altered my success rate and thinking about how to use that knowledge to improve the next batch of tricks. I had to be very strategic and decide well in advance what to test because, as mentioned earlier, I was recording magic tricks four at a time, and could only apply the lesson learned to the next batch of magic tricks.

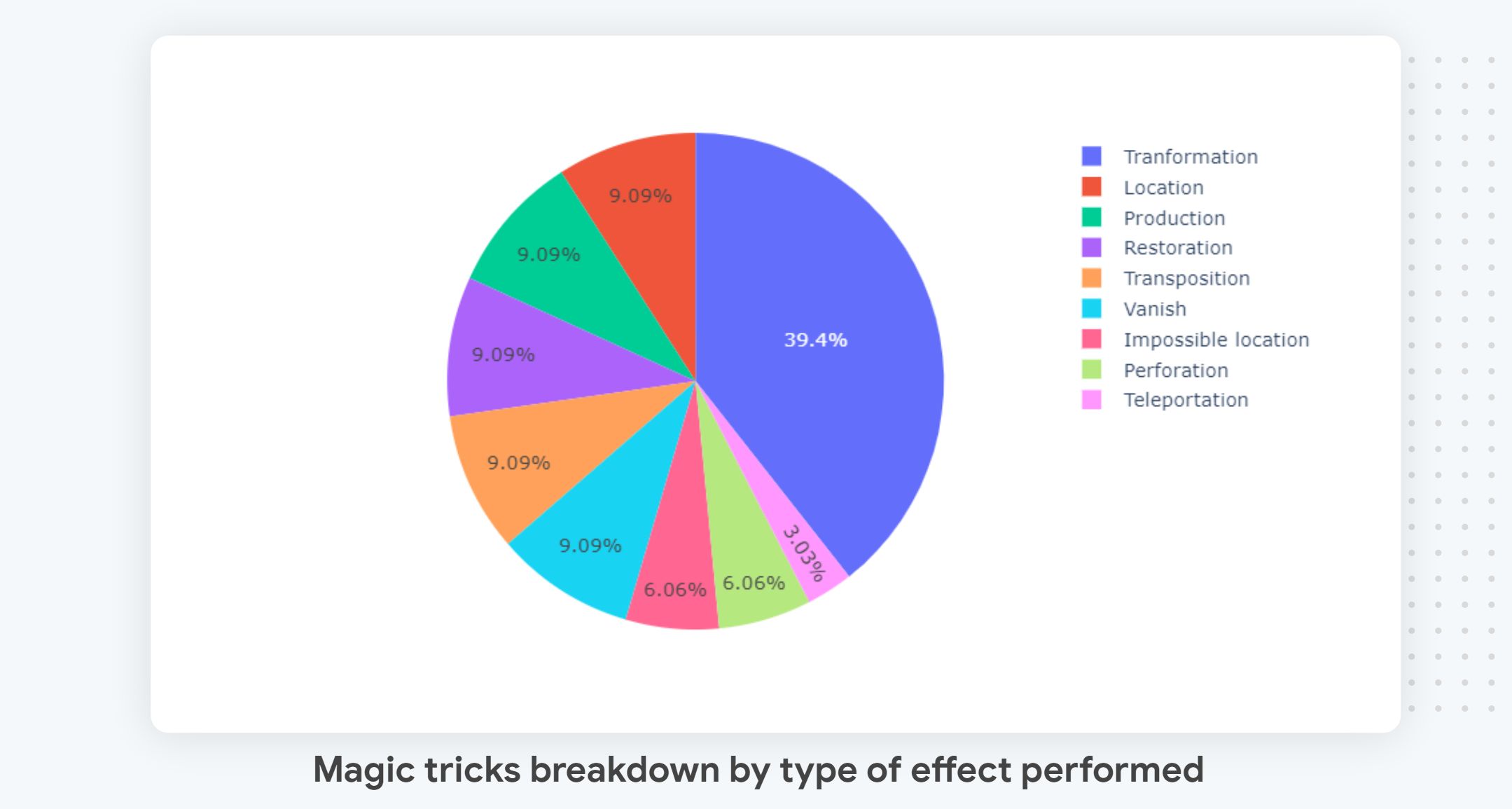

All in all, as you can see in the chart above, the most important success factor from that point on ended up being the type of magic I performed. There were other factors, such as the duration of the trick, how clear the plot was, and the type of prop used (people prefer cards), that made a difference, but nothing made as drastic a difference as the type of magic used. This factor also happened to be the hardest to alter, as I had to relearn how to do magic to succeed…

The worst showman: February

In February, I turned to what’s called stage magic, or grand illusion, which is what you see when you go to a live magic show. Until I started this project, I had never felt like performing this type of magic, because I find many of the tricks to be kitsch, and I don’t enjoy it unless it’s done by true masters such as Penn & Teller, David Copperfield, Matt Franco, or Shin Lim and Piff the Magic Dragon (go see their show if you can, they are awesome!).

However, I reasoned that stage magic might work well as these tricks were designed to be seen from afar. So I decided to keep an open mind and give it a go. Back in December, I had bought the props I needed to record a few of the ones I liked best, so I spent a few days during winter break recording them and aired them in February. In terms of artistic direction, I made sure to make these tricks upbeat, as fun as possible, and as accessible as possible. For example, I started to add a label with cartoon police on some of the props, like the Magic Tube trick you can see above.

Low and behold, Instagram agreed with me: Those tricks were kitsch and my engagement rate dropped to its lowest point, with barely 1.2% of viewers liking the tricks. Doing stage magic and trying to be fun was not working; yet another change of direction was in order.

Magic reloaded: March

In late February, when the ratings were crashing and the project turned into a dumpster fire, I had been actively working on the next generation of tricks for March. The good news was that with more than 25 tricks released at that point, I had a pretty good idea of what would work. The bad news was that I hated the answer: Visual magic was likely the only viable way to be successful. I had to accept the reality and focus on addressing users’ needs instead of focusing on what I liked. I have seen countless projects fail because people just couldn’t bring themselves to go in the direction the metrics suggested they should.

Fortunately, at that stage, I was of the mindset that this project had to succeed no matter what, so I decided after the mid-February retrospective that if visual magic was the answer then visual magic was what I would do.

Visual magic (aka online magic) is a type of magic trick that only works in front of the camera. I really didn’t want to do this type of trick because these tricks can’t be done in front of a live audience, require extensive setup, don’t rely on reusable sleight-of-hand techniques, and are very finicky, which means that even more takes are necessary to make them look good. In other words, they are one time, very difficult to execute, throw-away visual wonders with no long-term value for the magician.

For example, in the trick above, I switch the face of the card twice in a row without any obvious move, something that you can’t do that cleanly in front of a real audience — It requires too much setup and is impossible to do consistently. Actually it’s so difficult to execute that while this take is my best, I still failed to change the back color to red at the end - I blew and nothing happen :(

Despite over 3h of attempts, I just couldn’t do the full sequence flawlessly. I would have kept going but the “extra” required to perform the effect broke and it took a good 2h to make those as well (I am not very good at art and craft) so I had to give up. In the real world, a single card change is what most magicians can do reliably/cleanly and that is enough to create a good moment of surprise.

Moving to visual magic did, as expected, improve the metrics (yay, data science works!), with the like rate climbing back to 3.17%. Not yet where it should be, but far better than the previous month’s miserable 2%. The project was finally back on track after five months of hell.

The last mile: April

Thanks to the Instagram/YouTube comments, I quickly diagnosed the reason why the magic tricks were not performing as well as expected: trick fatigue. At its core, as discussed earlier, a magic trick often depends on the element of surprise to astonish people, which is why you don’t repeat the same trick twice. There are a few tricks that are designed to be repeated, but those are the exception. So, to succeed, I would have to create magic tricks that the Instagram audience hadn’t seen before.

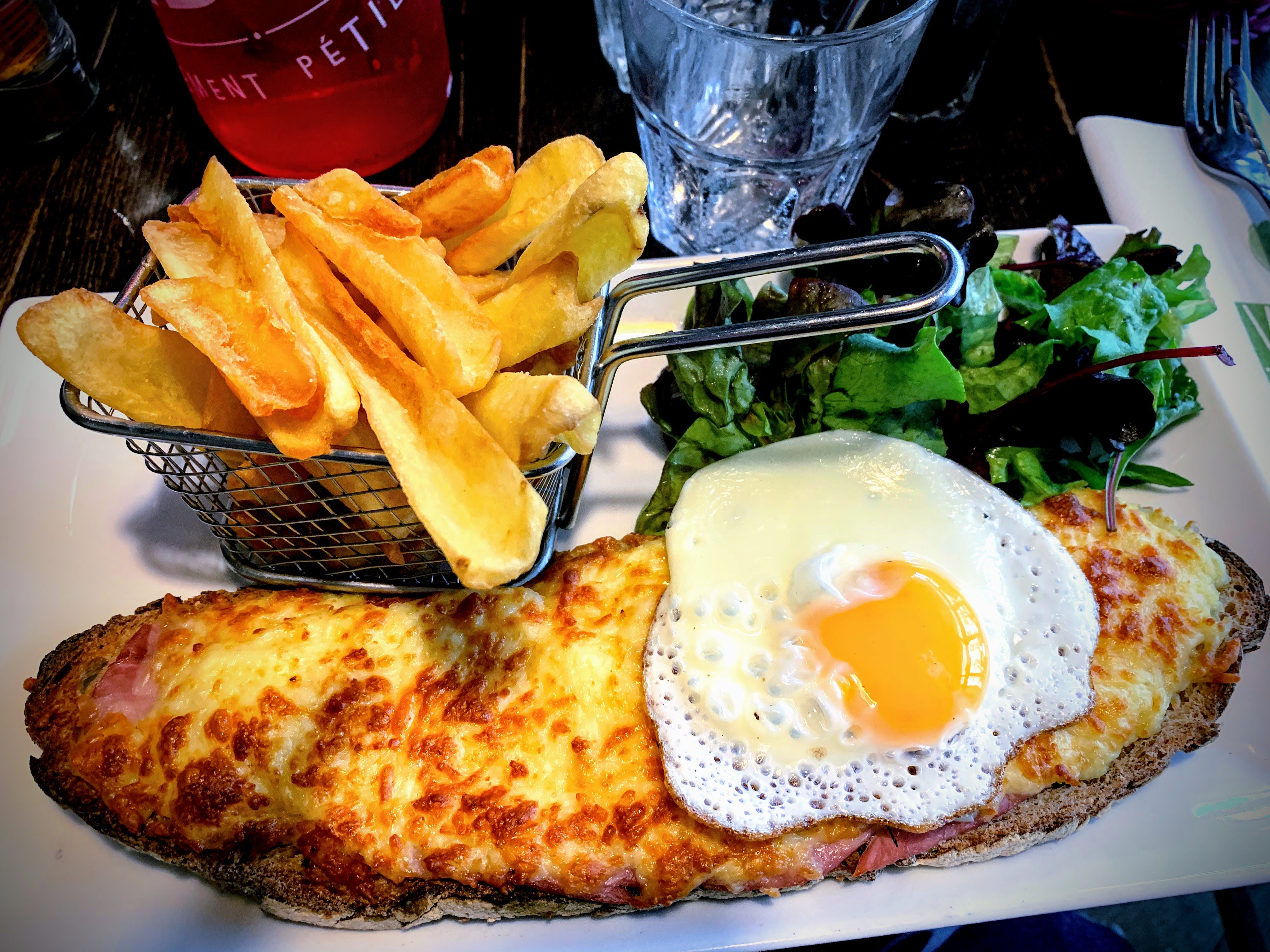

Creating new magic tricks doesn’t mean creating something completely new. Instead, you combine known principles, props, and techniques to create a trick that has a distinct narrative, plot, and visual flair. Very much like a great dish (like this wonderful croque madame from a Paris Cafe), a great magic trick is not only about the recipe and the ingredients but also how it is cooked and presented. It was about time I graduated from Instagram novice magician to become an accomplished mage who could produce flavorful tricks.

Producing distinctive visual magic tricks proved to be even more work than it had been before, because I had to spend much more time on the trick setup, the storytelling, and the video editing than before. For example, as you can see in the video above, during that period I created a magic trick that borrows from the Mandalorian universe that got an 8.39% like rate (8507 likes/101,403 views). The trick of losing a card and making it reappear on top of the pack is a fairly popular one on Instagram. What makes this version stand out compared to other Instagram versions is that it has the three key ingredients necessary to be successful on Instagram:

-

It’s deceptive: The reapparition is made under impossible conditions (yes, the coin is real) with no visible moves (it took me 10 hours of preparation and about 40 takes to get there…).

-

It’s fresh: The Mandolorian universe makes this trick different, thanks to its unusual color grading, distinctive music, and fun playing cards. To get to this level of customization was not easy: I had to order Star Wars cards specifically for this trick, handcraft the necessary “add-ons” so they would match the setting, and plan the music ahead of time so I knew exactly how much time I had.

-

It’s carefully paced: the trick has a clear plot that follows the music with each element introduced gradually to build suspense. I had to time myself very carefully to get the moves to match the music. I ended up discarding many attempts, as the execution was either too fast, too slow, or had too many superfluous movements that took away from the fluidity of the action.

Getting to that level of precision was stretching far beyond my abilities, and by late March, I was only able to work on two tricks at the time. The pandemic situation was rapidly improving, with the vaccination rollout picking up speed, and after 34 tricks recorded, I was ready to call it a day.

April would be my last month, with only four tricks published. I was hopeful (but quite uncertain) that I had finally cracked the code, and that those tricks would perform well. I felt a very deep relief that after months of failures and doubts, the like rate had finally soared past the 6% mark and reached 8%—ending the project on a high note.

What if I hadn’t met my goal in April Or, what if the vaccines had not been rolled out when they were? Well, the plan was to keep believing and go for even more visual magic—I had even started working on what would have been a good set of tricks that would have used CGI as the ultimate backup plan in case visual magic was not enough. However, I was really running out of mental energy so I am glad it worked out the way it did.

The project was finally a success and I was able to recognize that — it was one of those times when taking a win and leaving the table, rather than doubling down, is the smart play.

Epilogue

Even two months after the project ended, I still have ambivalent feelings about this project, as you can probably tell by now. On the one hand, the amazing engagement I got from Instagram viewers and the kind messages I received makes me feel that these tricks helped many people (at least a little) to get through those very difficult times. On the other hand, maybe I could have done something more useful with my time and money to help.

All in all, I got the chance to learn new things and to learn from my mistakes, so hopefully, I will do better in the future. In particular, I promised myself never to repeat the mistake of starting a project before I am absolutely clear what the outcome should be and why the project is important to me.

Thanks for reading this retrospective till the end. I hope some aspects of it will help you succeed in your own projects and that it offers a suitable epilogue to this adventure. If you enjoyed this post, please share it on your favorite social media so others might benefit from it. I spent a lot of time creating this content, and what keeps me going is the hope that it will be useful, so having it shared and read really means a lot to me. 😊

To get notified when my next post is online, follow me on Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn. You can also get the full posts directly in your inbox by subscribing to the mailing list or via RSS.

🙏 A big thanks to Aude, Celine, Emmanuel, Lidor, Masaru, Niels, Yuan, and everyone who took the time to send me a kind message—I couldn’t have done this without your support. Thanks, as well, to the millions who watched the tricks! I hope they made you smile and helped you at least a little in going through those difficult times.

À bientôt. 👋