This blog post exposes the cybercriminal groups that dominate the ransomware underworld, and analyzes the reasons for their success.

This is the third and final blog post of my series on ransomware economics. The first post was dedicated to the methodology and techniques developed to trace ransomware payments from end to end. The second post shed light on the inner workings of ransomsphere economics. As this post is built on the previous two, I encourage you to read them if you haven’t done so yet, or to read them again if your memory needs refreshing.

The findings presented in these posts were originally presented at Blackhat USA 2017, in a talk entitled “Tracking desktop ransomware payments end-to-end.” You can get the slides here and a recording of the talk is available on YouTube:

Let’s look at the cybercriminal groups that dominate the ransomsphere.

PC Cyborg – the precursor

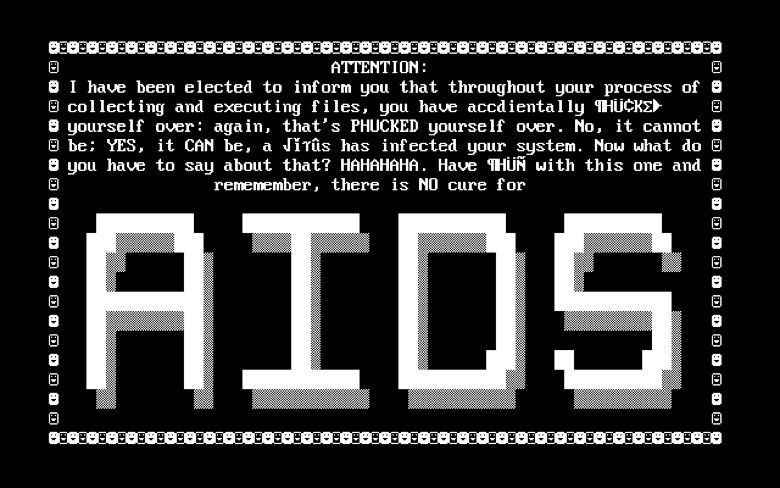

The first documented ransomware, the AIDS trojan, was unleashed in 1989 by the PC Cyborg cybercriminal group via floppy disks, way before most of us had even had the opportunity to touch a computer. It masqueraded as tool to help assess the risk of being infected by the AIDS virus, and used rudimentary cryptography which was easy to defeat. This ransomware asked for a ransom of $189 payable to the “PC Cyborg Corporation” at a PO box in Panama.

CryptoLocker - the rise of modern ransomware

CryptoLocker’s rise to prominence in 2014 marks a defining moment in ransomware history. This ransomware was one of the first (if not the first) to combine all the key technologies that constitute the foundation of all modern ransomware:

- Strong public key cryptography to encrypt user files. No flaw was found that would allow recovery of the files without paying the ransom. However, when CryptoLocker was taken down, a decryption tool based on the seized database was made available.

- Bitcoin as a means of payment. While CryptoLocker did offer other means of payment, it heavily promoted Bitcoin as the cheapest option for payment of the ransom.

- Timers to pressure users. CryptoLocker had a timer that let users know that their files would became unrecoverable within the next 72 hours, in an attempt to coerce victims to pay quickly.

While there was a lot of debate about how much the CryptoLocker group made, it was likely the first group to extort a million dollars( ~ $3M according to Wikipedia, ~ $2M according to our measurement). CryptoLocker was taken down as a part of Operation Tovar in 2014.

Locky – bringing ransomware to the masses

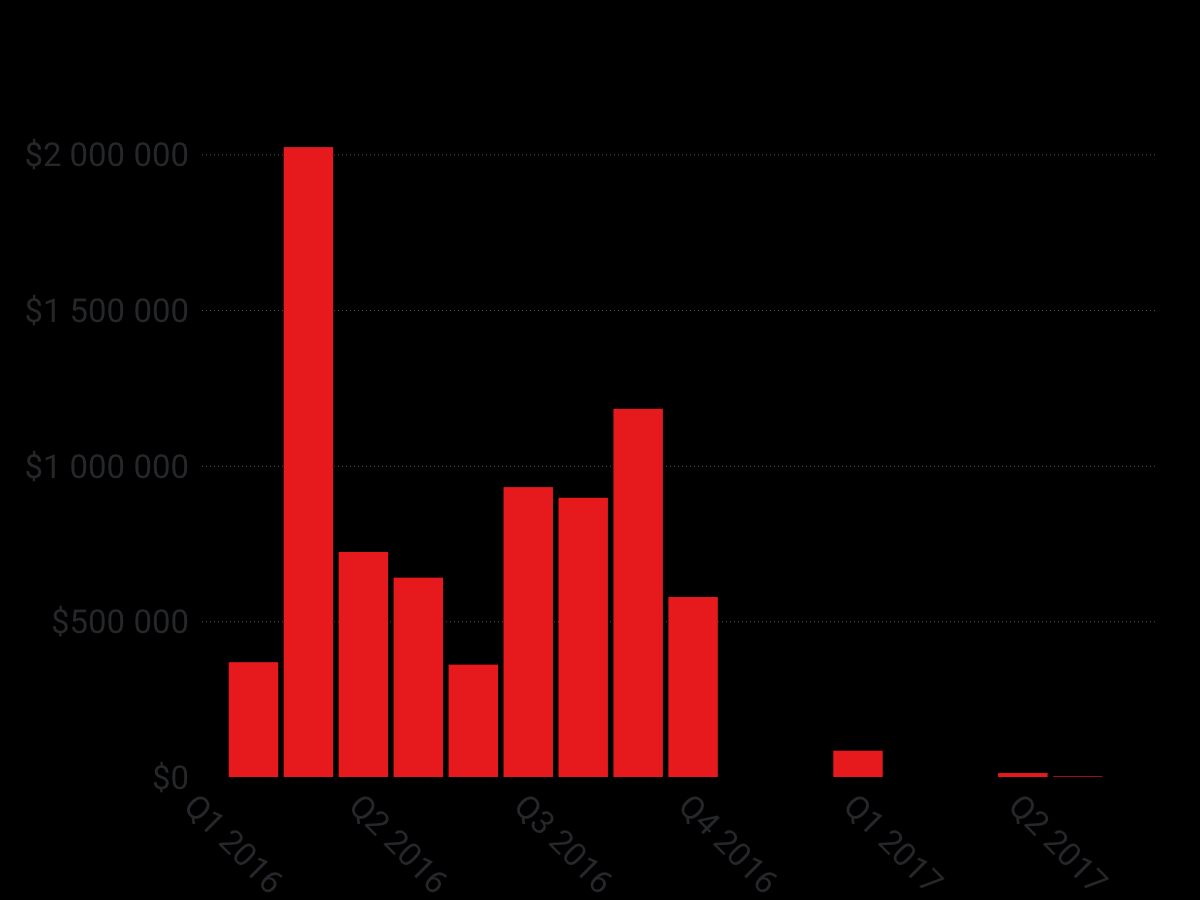

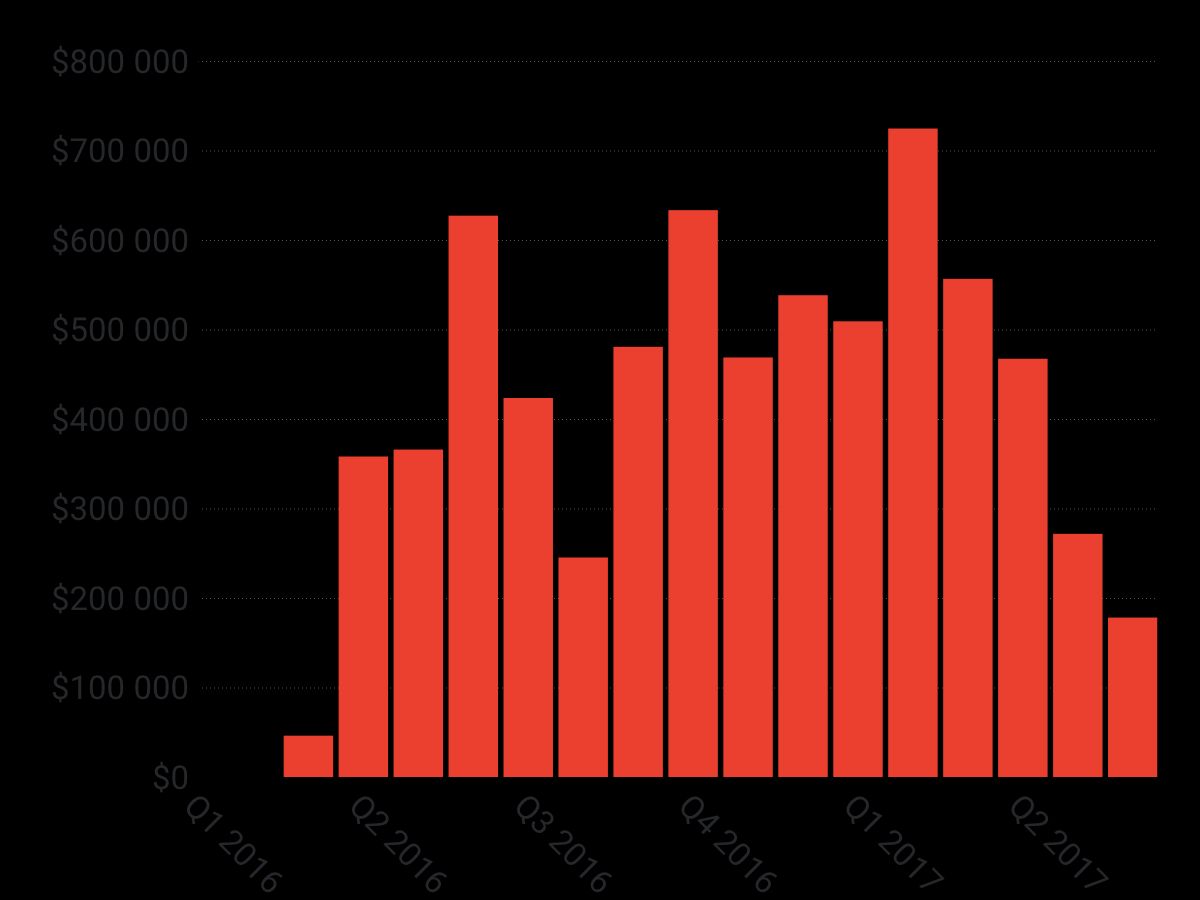

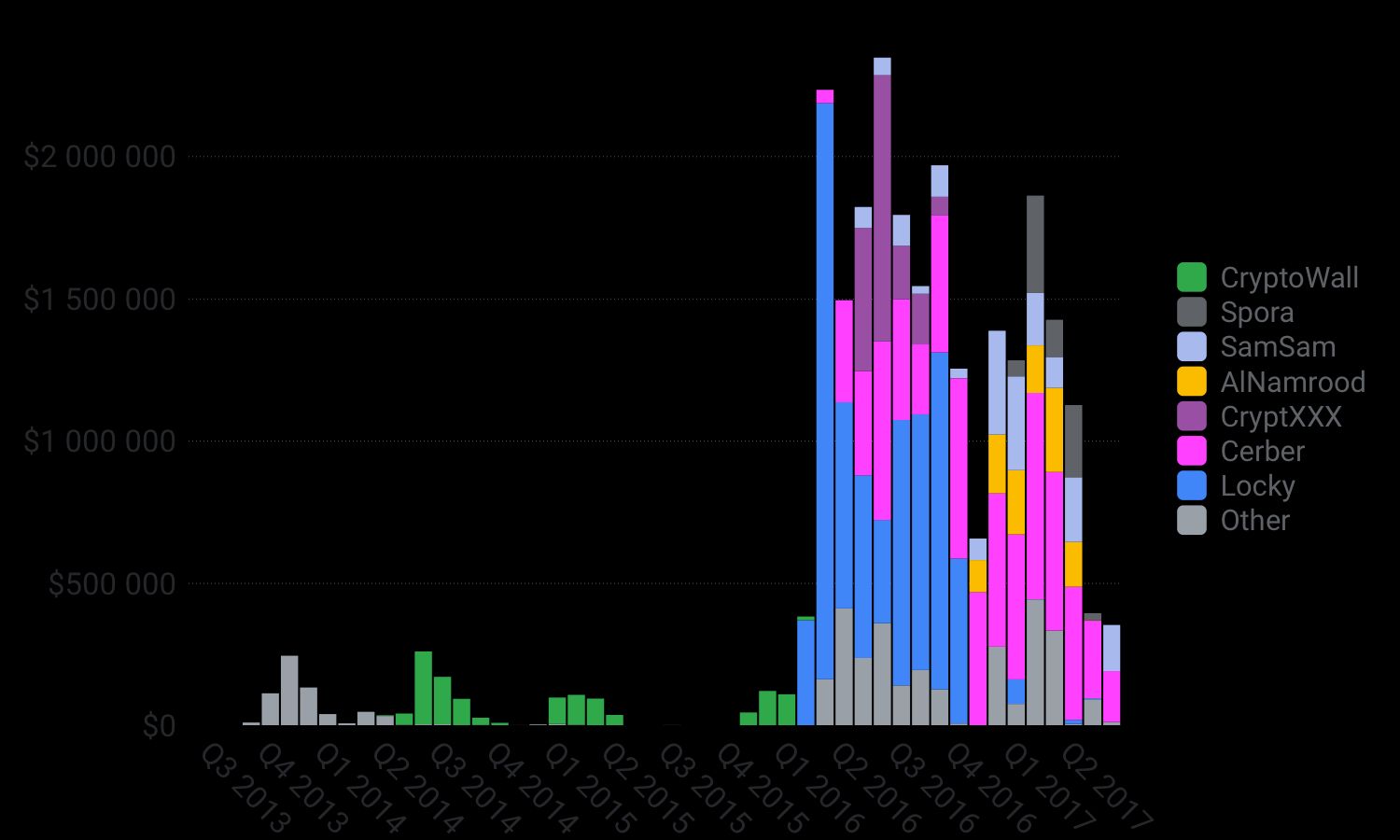

Locky was without a shadow of a doubt the 2016 ransomware king of the hill. As can be seen in the chart above, in 2016 Locky “earned” up to $2M in a single month, making it one of the few multi-million dollar earning ransomwares and maybe the biggest earner of all time, with close to $8 million in revenue.

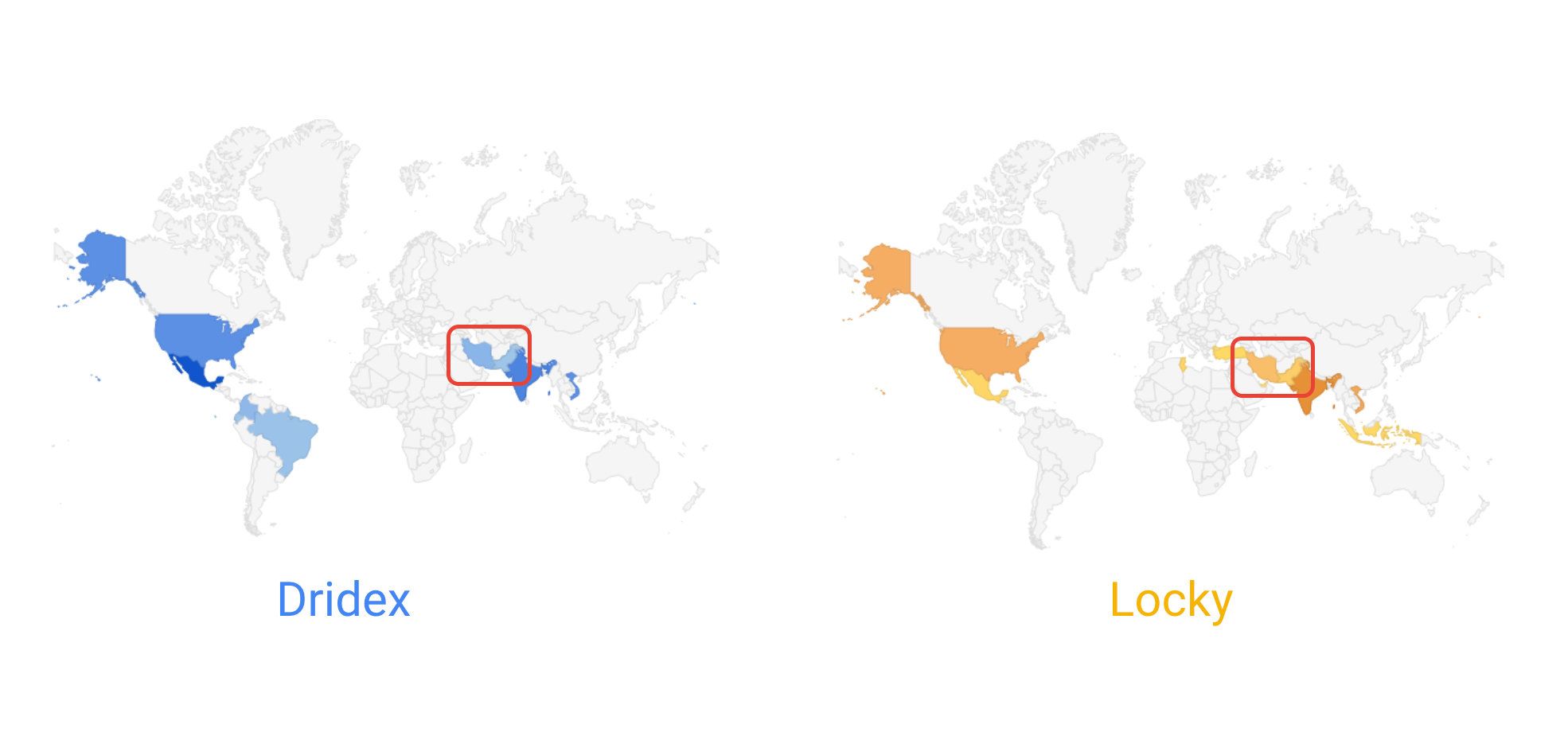

A key innovation that enabled Locky to scale its operations so widely was to use the infrastructure developed by other cybercriminals to distribute its ransomware payload. For example, on the Gmail side we saw Locky relying heavily on Necurs, a large botnet, to deliver its malicious payload. This botnet is also routinely used by other cybercriminal groups, including Dridex, a banking trojan. As a result, the overlap of infrastructure between Dridex and Locky is clearly visible in the map above, which geolocalizes the origin of malicious emails associated with the two groups as seen on the Gmail side sometime in 2016.

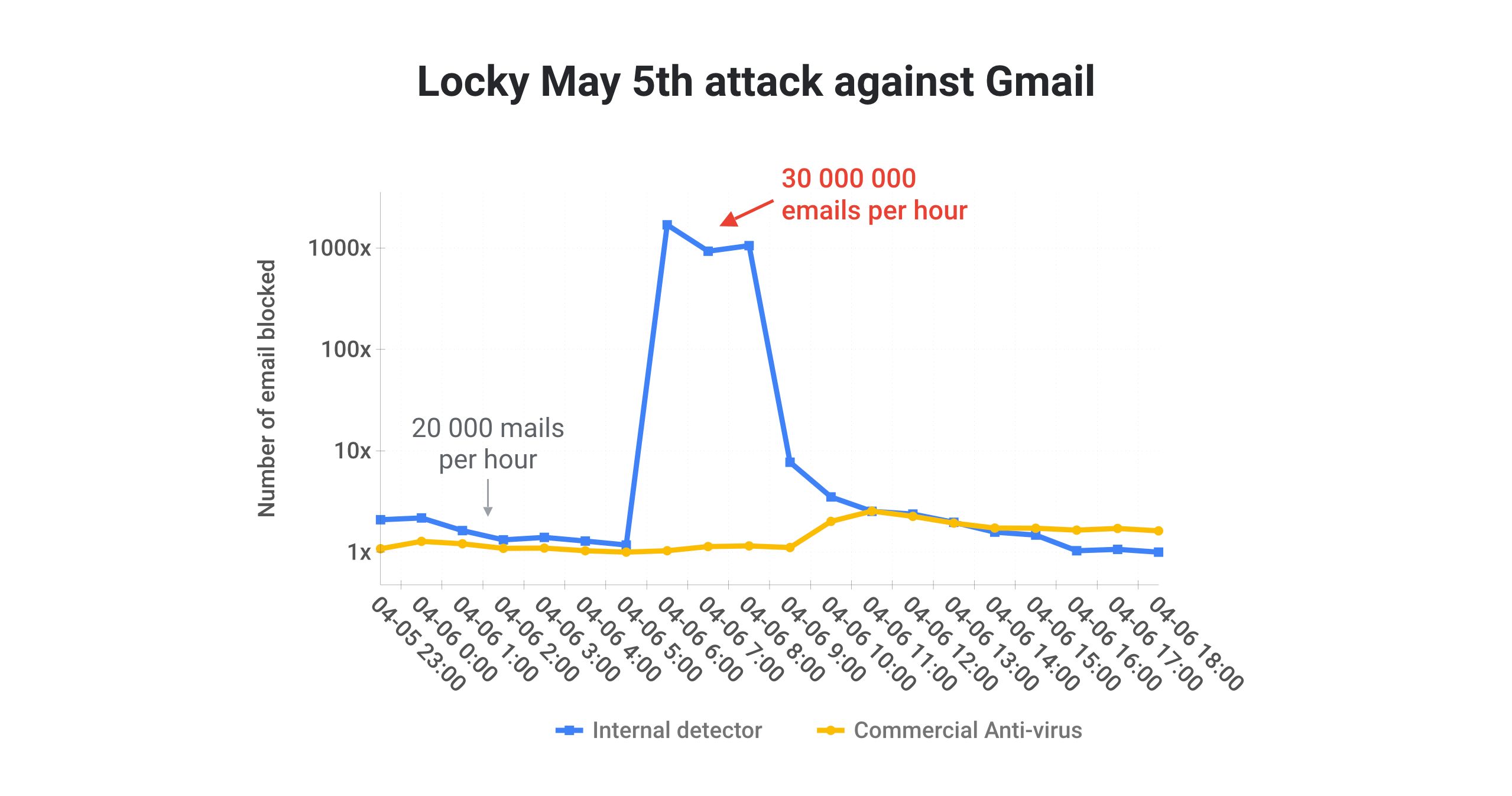

Making use of other cybercriminals’ infrastructure allowed Locky both to focus on its core business (developing and iterating the ransomware itself) and to send an unprecedented volume of malicious email. For example, as shown in the chart above, taken from my RSA presentation about attacks on Gmail inboxes, we routinely observed Locky sending over 100M malicious emails in a span of three hours.

So, to sum up:

Locky dominated the ransomware scene in 2016 by using other cybercriminals’ infrastructure to scale its operations, earning close to $8 million in the process.

Cerber – the rise of ransomware as a service

In 2017, Cerber overtook Locky as the king of the hill, thanks to its innovative affiliate business model. By using a ransomware-as-a-service model, Cerber allowed low-tech cybercriminals to jump on the ransomware bandwagon by offering a cut to anyone able to infect users. In turn, letting cybercriminals choose their own infection tactics allowed Cerber to diversify its distribution channels way beyond what Locky was able to do. This has allowed Cerber to generate the most steady source of revenue for ransomware ever seen. This revenue consistency is clearly visible in the chart above: in the last 15 months, Cerber has been able to generate at least $200,000 each month.

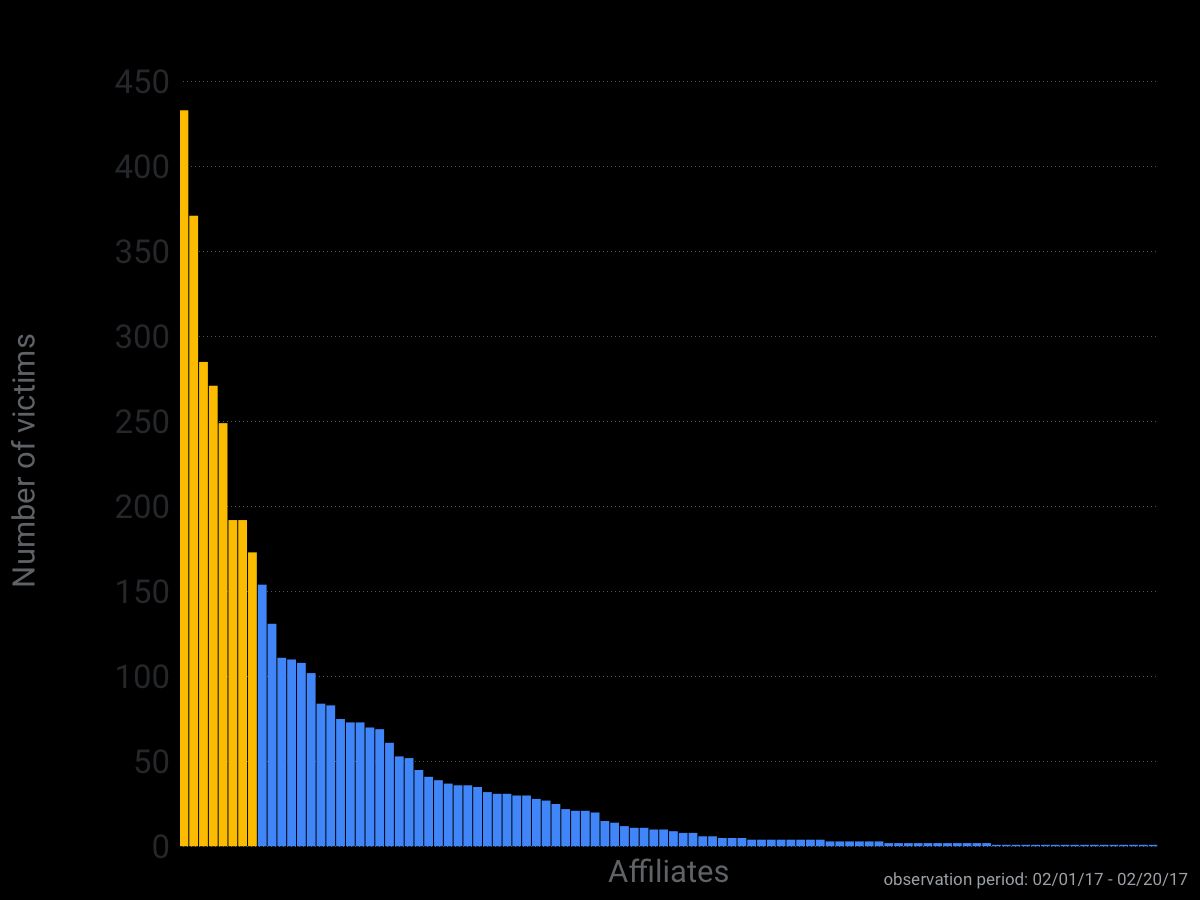

Thanks to one of our contacts, we were able to get some telemetry on Cerber’s affiliate distribution. Analyzing the distribution of infections per affiliate reveals some important pieces of information. Firstly, this telemetry confirms that the key to Cerber’s success was its ability to enroll hundreds of cybercriminals to help with the distribution of the ransomware. This trend can be seen in the chart above, which breaks down the infection of Cerber victims by affiliate over a two-week period in February 2017. Secondly, the telemetry shows that just a few affiliates account for the bulk of Cerber infections. This is somewhat good news because it means that stopping just a few cybercriminal groups could potentially significantly disrupt Cerber distribution.

Cerber became the largest ransomware family in 2017 thanks to its innovative affiliate model, earning close to $7M in the process.

The challengers – Spora et al.

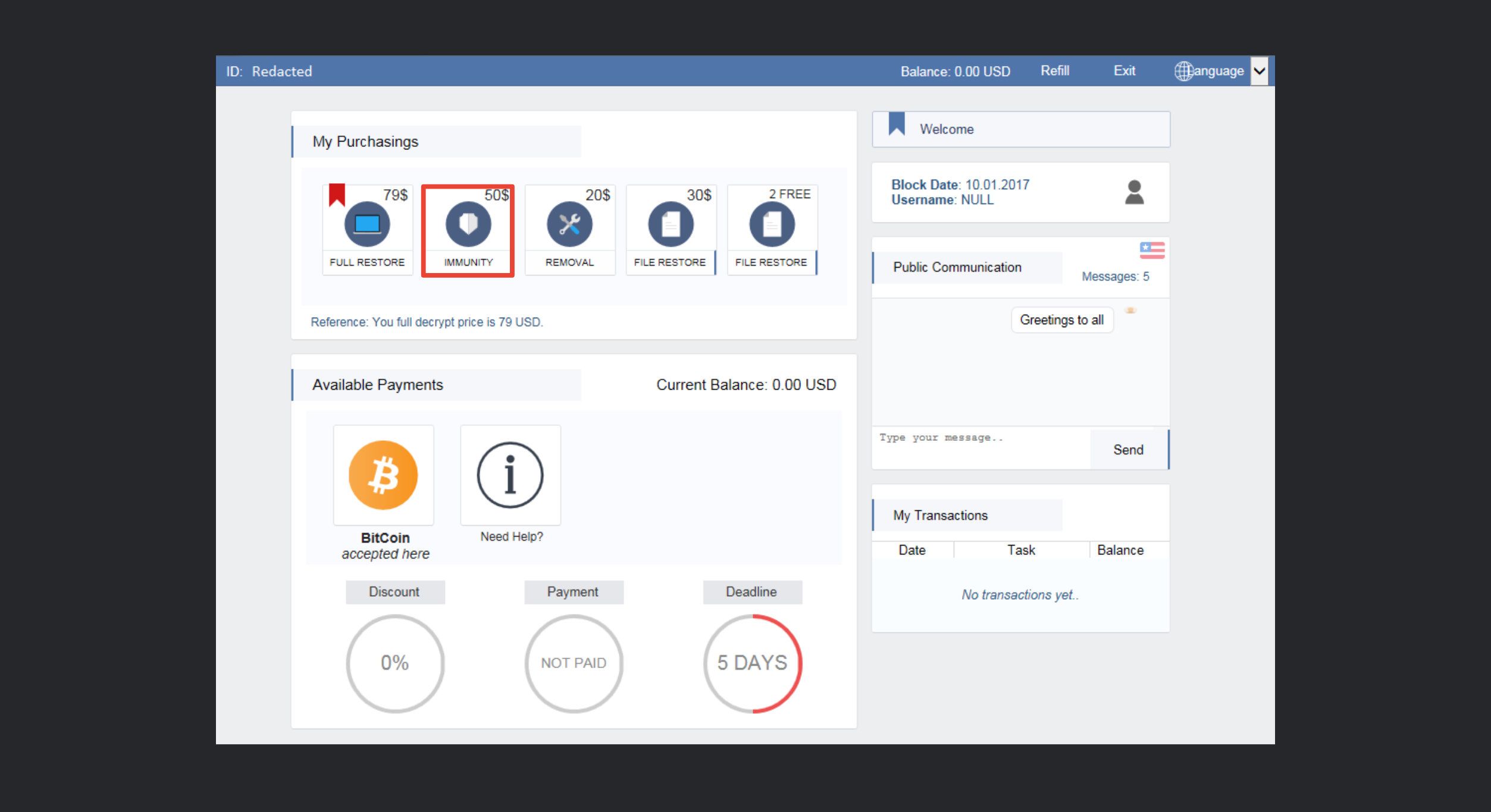

Starting at the end of 2016, we observed the rise of new ransomware able to offset Cerber’s market dominance somewhat, as shown in the figure above. Of the new challengers, Spora, SamSam and Al-Namrood appeared to be the strongest contenders, as they all nett˜s˜sed over $1M in revenue. These ransomware families were able to take a large market share by offering a few innovations, including a better “user experience”. For example, as visible in the screenshot below, Spora offers a very good UI with a lot of payment and decryption options for victims to choose from, which likely increased their conversion rate.

As of late 2017, the ransomware market is no longer dominated by a single ransomware group. Instead, there are a few actors who are trying to out-innovate their competitors. This competition, in conjunction with the large stream of revenue generated, is bad news for users as it drives ransomware authors to continuously improve their ransomware and distribution channels. It is unclear who will come out on top, especially with the recent return of Locky, the 2016 kingpin.

Ransomware are becoming increasingly sophisticated due to the intense competition between cybercriminal groups striving to improve their ransomware market share.

The impostors – Wannacry and Nonpetya

This post would not be complete without mentioning the rise of wipeware like Wannacry and Nonpetya, which masqueraded as ransomware. It is widely accepted that both were state-sponsored malware that attempted to disguise themselves as ransomware in order to muddy their attribution and potentially to delay investigations. Distinguishing between wipeware (which aims to destroy a victim’s files) and ransomware can be very difficult because there are only minor differences, and they mostly appear only after intensive reverse engineering.

The two telltale signs that malware is wipeware and not ransomware are:

- wipewares don’t save the key used to encrypt the files, and just use a random value as an encryption key, and;

- wipewares don’t bother to generate a Bitcoin wallet for each victim, which is needed to tie a ransom payment to a given infection.

In 2017 state-sponsored wipeware started mimicking profit-driven ransomware, in an attempt to conceal their true motive and delay attribution.

Thank you for reading this post till the end! If you enjoyed it, don’t forget to share it on your favorite social network so that your friends and colleagues can enjoy it too and learn about ransomwares.

To get notified when my next post is online, follow me on Twitter, Facebook, Google+, or LinkedIn. You can also get the full posts directly in your inbox by subscribing to the mailing list or via RSS.

A bientôt!