For South Asian women, a major hurdle to their meaningful participation online is their ability to ensure their safety. This post illustrates this challenge by recounting the safety and privacy challenges faced by women across India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, who talked to us about their online experiences. Overall, we find that women in the region face unique risks due to the influence of patriarchal norms and because fewer women are online.

This post is a summary of the large-scale study led by Nithya that our team conducted in partnership with many universities around the world and teams at Google. Its aim was to understand better South Asian women’s lived experiences. It is our hope that the results will help to better inform how to design products that truly enable gender equity online for all Internet users.

A comprehensive analysis of our study results is available in our award-winning CHI’19 paper and Nithya’s award-winning SOUPS paper from last year. We choose to highlight the two papers together as they share many authors and the same pool of participants.

This post, after providing a short background, covers the following topics:

- Device privacy challenges: This section outlines the privacy challenges faced by South Asian women when using their smartphones.

- Online safety challenges: Highlights the risks and abuse faced by South Asian women when using online services.

- Design considerations to promote gender equity: When building products, features that mitigate the risks would help to improve the safety of South Asian women.

Background

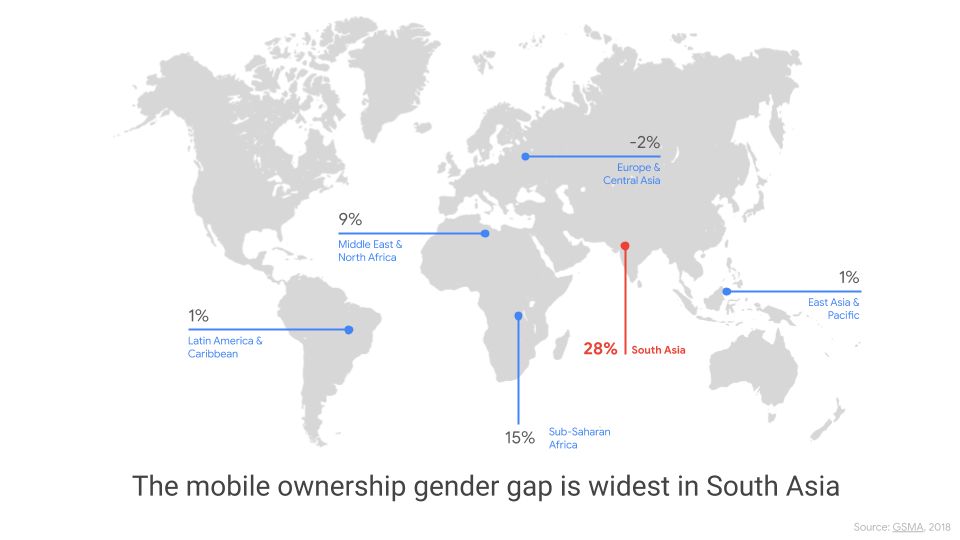

As a region, South Asia has one of the world’s largest populations—India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh alone are home to over 20% of the global population. The region is also one of the fastest-growing technology markets as a result of increased infrastructure and growing affordability. Despite this progress, South Asia faces one of the largest gender disparities online in the world: women are 28% less likely to own a phone and 57% less likely to connect to the mobile Internet than men.

For South Asian women, a major challenge to their meaningful participation online is the ability to ensure their own privacy and safety. South Asian women often share their devices with family members for cultural and economic reasons. For example, gender norms might result in a mother sharing her phone with her childrens (whereas the father might not). Today’s features, settings, and algorithms do not fully provide a good on-device privacy model for shared devices.

Abuse on applications and platforms also poses potentially life-threatening risks that further prevent women from participating online in South Asia. For example, Qandeel Baloch, a social media celebrity in Pakistan, was murdered by her brother for posting selfies online. She was one of the 5000 to 20000 women who are victims of “honor killings” every year.

In a separate event, a 21-year-old woman in India committed suicide after her social media profile photograph was stitched to a semi-nude body and spread virally.

While online abuse is not limited to South Asian women, the risks are often heightened for this community, due to the influence of patriarchal norms and because fewer women are online.

Method

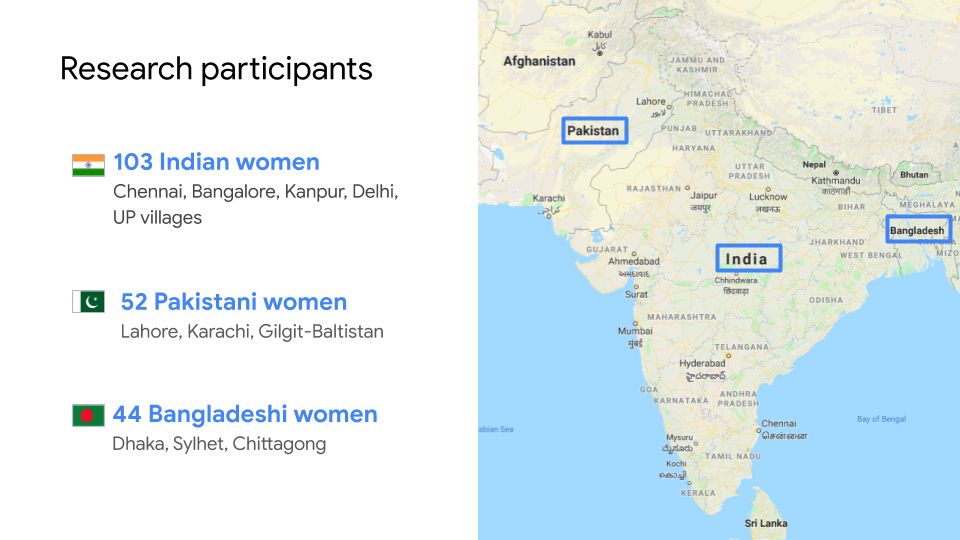

To understand some of the challenges that South Asian women face online and on their devices, between May 2017 and January 2018, the research team conducted in-person, semi-structured, 1:1 and triad interviews with 199 participants who identified as women in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh (11 of them identified as queer, lesbian, or transgender male-to-female).

Six NGO staff members working on women’s safety and LGBTQ rights were also interviewed. Participants included college students, housewives, small business owners, domestic maids, village farm workers, IT professionals, bankers, and teachers.

The interviews, conducted in local languages, spanned 14 cities and rural areas. There were 103 participants from India, 52 from Pakistan, and 44 from Bangladesh. To protect participant privacy, the names used in this post are pseudonyms.

Device privacy challenges

This section highlights the main device-related privacy challenges faced by our participants based on an analysis of the interview data.

“Like jeans and dating”: Privacy has value connotations

Our participants perceived the term “privacy” in various ways. Some viewed it as a Western import, like “jeans and dating” are, that was in direct collision with their cultural ethos of openness. Many of our lower- and middle-income participants told us that: “Privacy is not for me, it’s for those rich women,” implying that privacy was for upper-class families where social boundaries were presumed to be acceptable.

However, as discussed later in this post, all of our participants, regardless of their social or economic background, employed techniques to maintain what we would describe as privacy, while sharing devices in line with local norms.

Device sharing is common and valued

Our participants expressed a cultural expectation that they, due to their gender roles as caregivers, would regularly share their devices and digital activities with social relations in three main ways:

- Shared usage was when children, family members, friends, or colleagues borrowed someone’s phone. Women’s mobile phones were often viewed as family devices.

- Mediated usage was when someone set up or enabled a digital experience for a less tech-confident user, often due to technology literacy and gender roles (e.g., a daughter might search for and then play a video for her mother).

- Monitoring was when someone else checked messages, content, or apps on a person’s phone, without otherwise having a need to use the phone. About half of the participants thought it was acceptable to have their phones monitored by others to avoid viruses or unwanted attention online, but the other half felt coerced.

Privacy-preserving practices in device sharing

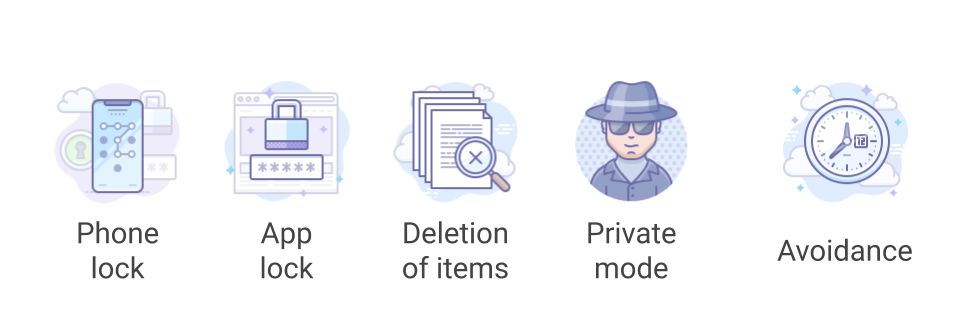

Regardless of value assignments to privacy, all participants in our study—no matter their social or economic background—employed some of the following techniques to maintain a degree of privacy while sharing devices in line with local norms.

Phone locks

Altogether, 58% of our participants regularly used a PIN or pattern lock on their phones to prevent misuse by strangers or in case of theft. Phone locks can be an overt, effective strategy in many contexts; however, they were seldom effective in preventing close family members or friends from accessing a woman’s phone.

App locks

Another commonly used, semi-overt technique for privacy was app locks—applications that give a user the ability to password- or PIN-protect specific applications, content, or folders. In total, 29% of our participants reported that app locks provided more granular control than phone locks, but did not provide the secrecy they sometimes desired from friends and family. The very presence of an app lock icon or login sometimes led to questions like: “What are you hiding from me?”

Overall app locks allowed participants to share their devices, instead of needing to make a blanket refusal, by providing granular control over specific apps or content. Most participants hid social media applications, photograph and video folders created by social applications, and Gallery (a photograph editor and storage folder). A few participants reported hiding other applications, like menstrual period trackers, banking applications, and adult content folders.

As Gulbagh (a 20- to 25-year-old college student from Multan, Pakistan) described:

“I have enabled app locks in addition to the phone lock. I have it on WhatsApp, Messenger, and Gallery because sometimes friends share some pictures and videos with you that are only meant for you [smile]. My brother is never interested in my phone but it is my younger sister who is a threat [laughs]. So I have an extra shield of protection.”

Deletions

As a more covert action, participants would delete sensitive content from devices that traveled freely between various family members. This included aggregate deletions to delete entire threads or histories of content, and entity deletions to delete specific chats, media, or queries.

Participants reported using aggregate deletions (16%) when they were unable to find a way to delete a specific piece of content, wanted a large amount of their content deleted (e.g., browsing history, search history, or message history), or believed their phones were slowing down. They used entity deletions (64%) to remove individual items—such as a single text message, photograph, or a previously searched term—to manage what others who shared or monitored their phones would see.

For example, Maheen (a 20- to 25-year-old housewife from Lahore, Pakistan) described her rationale for deleting specific photographs and videos:

“When I open [social media] chat, sometimes my friends send inappropriate videos. Sometimes they send boyfriend photos. Then that will lead to questions from elders like: “Where did you go?”, “Who have you been with?”, and “Who is that man?” So it is better to delete the chats and avoid misunderstanding.”

Mothers often needed to manage their content histories when sharing with children. For example, Sahana (a 40 to 45-year-old accountant in Delhi, India) told us:

“I would never want my son to watch anything that is inappropriate. Sometimes, I receive videos from friends that are vulgar for children, then I immediately delete such videos.”

Entity deletions in personalized systems were particularly challenging for many participants to discover and manage. For example, Shaina (a 35- to 40-year-old medical representative in Kanpur, India) described how she managed her recommendations through algorithmic hacking: “When I watch a video that is little bit not nice, then I search for five or six other videos on different topics to remove it.”

Private mode

Overall, we found that private modes were used by technology-savvy and censorship-conscious participants. For example, Mary (an 18- to 25-year-old engineering college student in Bangalore) said: “I have used hidden mode a few times, like when reading the Fifty Shades of Grey ebook on my phone.”

The majority of participants were not aware of what private modes in web browsers did or where to find them. The two major reasons why our participants did not use private mode were:

-

The terms used to refer to private modes were not always intuitive to participants.

-

Private modes are often associated with secret activities, potentially threatening participants’ values of openness as they perform their culturally appropriate gender roles.

Avoidance

We found that our participants avoided installing some applications on their phones to prevent questioning by or accusations from co-located household members. For example, 24 participants stated that they had a bank account hidden from their husbands. The balances had been built up over time from the small amounts left over from the monthly budget or their salary. Many of those participants avoided installing a banking app on their devices, due to low trust in their ability to control the app’s visibility.

Similarly, certain types of digital content or applications were entirely avoided in households with children, like gynecological videos, for fear that the children would eventually figure out the password or PIN for the app lock.

The culture of avoidance is pervasive even in social media interactions. For example, Lathika (a 45- to 50-year-old banking professional in Bangalore) noted:

“We just call and talk to each other. Everyone in the [social media] group knows that the phone is in the midst of the family. So we don’t send anything to each other awkward or secretive at any time of the day.”

Many of our participants used an avoidance strategy we coined making an “exit.” Performing an exit is suddenly closing an application due to contextual sensitivities (i.e., who was around). Participants reported using exits when they saw embarrassing or sensitive content and wanted to avoid social judgment.

For example, Sonia (an 18- to 25-year-old arts student in Chennai, India) reported:

“Quite often I am watching something on the Internet and suddenly a porn ad or video pops up. I immediately lock my screen in that case and look around to check if anybody has seen this or not. I then open it again when nobody is around, view it, and then delete or close it. My brother and parents would definitely not like the idea of me watching porn.”

While such exits do not remove the recorded history of the content presented, some participants believed they did, which presents an opportunity to help them understand what information is captured and stored, and where.

For more details of the device-sharing practices including the associated privacy challenges experienced by South Asian women, read Nithya and Sunny’s paper.

Online safety challenges

The majority (72%) of our participants reported experiencing digital abuse, such as unwanted messages or the non-consensual release of information about them, especially on social media platforms.

The real-world consequences of online abuse

Due to the societal structure in South Asia, online abuse can harm a woman’s perceived integrity and honor, as the onus of a family’s and community’s reputation often rests on women in South Asia. As a result, in many cases, a woman who has experienced abuse is often presumed to be complicit. Emotional harm and reputational damage were the most common consequences reported by participants (55% and 43%, respectively).

The tight-knit nature of the hyper-local communities where many abuse incidents have occurred sometimes lead to real-world repercussions that include domestic violence or loss of marriage opportunities, according to our participant testimonials.

The viral nature of abuse carried via social media platforms further exacerbated the pressure felt by participants and increased their distress. As an extreme example, this social pressure may push a victim to commit suicide. For example, a 21-year-old Indian women hanged herself after doctored pictures showing her as scantily clad were shared on Facebook.

Online abuse looks materially different in South Asia

Some content that may not be perceived as sensitive in many Western cultures can be considered to be very sensitive in some South Asian contexts. For example, sharing a photograph of a fully-clothed woman or even mentioning a woman’s name, in the wrong context, could lead to serious negative consequences for the woman in parts of South Asia.

Raheela, an NGO staff member for a women’s safety helpline in Pakistan, explained:

“Sharing a girl’s picture may not be a big deal for U.S. people, but a fully clothed photo can lead to suicide here in conservative regions of Pakistan.”

Our participants were concerned that most online platforms did not consider the South Asian cultural context when reviewing abuse complaints. For example, sharing a photograph of someone fully clothed might not violate platform policies, even when it is being used to abuse someone.

Types of online abuse experienced

Based on our interviews, we identified three main types of online abuse experienced by our participants.

Cyberstalking

In total, 66% of our participants experienced unwanted contact—mostly sexual in nature—including daily calls, friend requests, and direct messages from unknown men. The frequency of such contacts is exacerbated in part by social platforms and communication tools, such as instant messaging, that make it easier for strangers to reach out.

For example, Mishita (a 20- to 25-year-old garment factory worker from Dhaka, Bangladesh) explained that those unwanted calls led to her parents suspecting her of engaging in relationships with men:

“I get these calls a lot. Mainly after I recharge [top-up] my phone at the shop. It’s so irritating. I tell them I am married, have a baby, but still they call. My father asks me, “Who is calling you so many times, is it a man?”

Impersonation

Altogether, 15% of our participants had experienced having an abuser forge content portraying them without their consent. The incidents reported included the creation of synthetic porn where the abuser would stitch their faces onto pornographic material, and the stealing of their identity to create a fake social profile that was embarrassing.

Often, it was not until after negative repercussions from their community that participants became aware that their identities had been misappropriated. For example, Mariyam (an 18- to 25-year-old gym trainer in Lahore, Pakistan) told us that when she was in 12th grade, an abuser stole her profile photograph and identity to create a sexually revealing, false profile without her consent. She realized something was wrong only when her male classmates started to make sexual gestures toward her out of nowhere and the school principal rebuked her “loose character.” Her family ended up being blamed for raising a morally corrupt daughter.

Personal content leakages

In total, 14% of our participants had had an abuser who non-consensually exposed their online activities in unwanted social contexts. Abusers turned ordinary interactions, such as friendly chats and normally innocent photographs, into harmful content by leaking them in unwanted contexts, such as to participants’ elderly relatives, employers, or the public. Some went as far as using this content for blackmail.

Overall, we found that personal content leaks were the most damaging of the three types of abuse reported in our study, principally due to the harm they caused to participants’ social reputation and dignity. For example, Chandra (a 25- to 30-year-old from Delhi, India) told us how she was blackmailed by a male stranger who took advantage of the fact that in South Asia, cross-gender interactions were not always socially accepted: “[He said:] ‘Talk to me every day or I will tell your family that you were talking to me.’”

How to design online products and services that promote gender equity

While there are no silver bullet solutions to prevent online abuse, there are a few key steps that online products and services can take to help promote gender equity:

-

Carry UX research to understand the various types of defense mechanisms that might be helpful to all of your users, and implement them. For example, your users might strongly benefit from the ability to perform entity and aggregate deletions, to use private modes to prevent certain activities from being stored, and from blocking. For example, both Google Maps and Amazon search allow users to delete search queries.

-

Ensure that defense mechanisms are easy to find and understand. Key to this is conducting high-quality user research with participants who represent your user base (which might include multiple studies across cultures) and working with expert UX designers and writers. Both methods will help to ensure that your users are likely to find and understand the features and know how to use them.

-

Make sure social context is taken into account when abuse is reported. As noted above, very often social context is what makes online abuse in South Asia different and more dangerous. Thus, it is important to have a report process and training material that take cultural context into account, so that a report of what might seem harmless in one country (say, a picture of someone fully clothed) is still acted upon, as it may be a real problem in the victim’s location.

-

As a community, it is also our duty to help create safe online places by providing privacy option such that takes into account the socio-cultural differences. We also need to ensure that those differences are accounted for in online community guidelines and that they are respected, so that everyone can participate safely, irrespective of their gender, origin, or beliefs.

Thank you for reading this blog post till the end! Don’t forget to share it, so your friends and colleagues can also learn about the online challenges faced bu south asian women. To get notified when my next post is online, follow me on Twitter, Facebook or LinkedIn. You can also get the full posts directly in your inbox by subscribing to the mailing list or via RSS.

A bientôt!